|

|

|

Volume XI |

April 2006 |

Number IV |

|

|

Rio Arriba County Institutes Communication Tower Moratorium in Response to Community Concern By Kay MatthewsANNOUNCEMENTSEditorial: Is the Forest Service Prepared? By Kay Matthews |

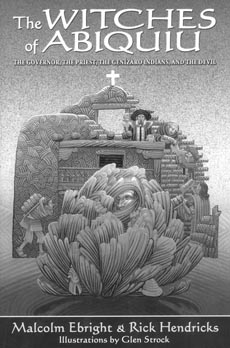

Agriculture Revitalization Initiative By Mark Schiller and Kay Matthews (with Paul White and Lynne Velasco) Book Review: The Witches of Abiquiu: The Governor, the Priest, the Genízaro Indians and the Devil By Malcolm Ebright & Rick Hendricks Reviewed by Kay Matthews Camino Real Gets New District Ranger By Mark Schiller |

Rio Arriba County Institutes Communication Tower Moratorium in Response to Community ConcernBy Kay MatthewsIt's disconcerting to wake up in the morning and find that your familiar environment has been invaded by a foreign structure you didn't know was coming. But when it's a cell phone tower erected on a dirt hill above your house, the Presbyterian Church, the Santuario, and the Chimayó Community Center, it's more than disconcerting, it's a desecration. Consequently, the community quickly organized and resurrected the Chimayó Council on Wireless Technology that successfully persuaded the Española School Board in 2004 to prohibit the construction of cell phone towers on 11 school sites in the Española Valley.

The offending T-Mobile tower on its barren hillsite The folks who are active in the Chimayó Council on Wireless Technology represent a cross-section of the community and therefore bring a variety of concerns regarding cell phones to the table. Some believe that the microwave radiation released by the towers and cell phones is responsible for numerous heath problems including fatigue, irritability, headaches, dizziness, nausea, loss of appetite, sleep disturbances, memory loss, skin problems, cardiovascular problems, low sperm count, and most disturbing, brain cell damage that could conceivably leave an entire generation of users suffering from mental deficiency or Alzheimer's disease. Others are concerned that cell phone towers, regardless of whatever health problems they may or may not cause, do not belong in residential neighborhoods and particularly in a Chimayó neighborhood that is the heart of the community: the tower sits on a hill above the intersection of SH 76 and County Road 98 where the cluster of Ortega and Trujillo weaving shops, the Benny Chavez Community Center, Rancho de Chimayó, El Santuario, the Chimayó Museum on the historic plaza, and the Presbyterian Church define the culture of Chimayó. The recent reconstruction of SH 76 from Chimayó to Córdova and the construction of the tower are testimony to a modernist vision that doesn't sit well with those who want to make sure that in the rush to join the 21st century Chimayó doesn't abrogate its responsibility to maintain its cultural and historical tradition. Council member and former state historian Hilario Romero stated at an organizing meeting, "One thing that's often overlooked in these kinds of struggles is a sense of community, which includes issues of health, beauty, wildlife, and the democratic process." He suggested that the group look into obtaining the designation of Historical Village to begin a process whereby structures like cell phone towers would be more rigorously regulated. He also cautioned that as more and more communities allow wireless technology to run rampant throughout their environs (Rio Rancho is considered the Wi-Fi capital of New Mexico) the question of privacy comes into play as this technology can facilitate wire tapping. On March 30 the community succeeded in peti-tioning the Rio Arriba County Commission to impose a nine-month moratorium on the construction of cell phone towers in the county until a new ordinance that regulates all communication towers in the county is drafted. Members of the Council presented their case admirably to an obviously sympathetic commission. Raymond Bal, who operates El Potrero Trading Post next to El Santuario, gave the commissioners a petition signed by 300 people opposed to the new cell tower that he described as "ugly, wrong, and unfair to the residents of Chimayó." He also pointed out that while the current Rio Arriba ordinance allows towers below 70 feet to go through only an administrative process (towers over 70 feet must go through a permitting process with public review, etc), the new tower sits on a hill above SH 76 that rises approximately 80 feet, which in effect makes the height of the tower 150 feet. When the commissioners later quizzed Planning Director Patricio Garcia as to whether his department had taken this into account when they authorized the tower, he replied that it hadn't.

Members of the Chimayó Council on Wireless Technology who testified before the County Commission Chellis Glendinning, author of the book When Technology Wounds and a psychologist, spoke about the potential health issues of electromagnetic radiation and the denial of telecommunications corporations, with the complicity of the media, about these issues because of the enormous economic investment they have in cell phone and other wireless technology. She got a big laugh when cautioning the commissioners that research has shown that men who wear their cell phones on their belts suffer lower sperm counts. Others who spoke included: Lorraine Vigil, executive director of the Chimayó Museum; Hilario Romero, who pointed out that the spiritual significance of the Chimayó pilgrimage to the Santuario is known all over the world; Arthur Firstenberg, an expert on electromagnetic radiation; Raymond Chavez, former county commissioner and brother of Bennie Chavez, after whom the community center is named; and Deirdre McCarthy, who read letters from a native New Mexican and her son asking why T-Mobile had stealthily erected its tower with no community notification. In an article in The New Mexican a spokesperson for T-Mobile claimed that the company had indeed contacted the community about its plans to erect the tower. Unfortunately, when that community, in the voice of Lorraine Vigil, told T-Mobile in no uncertain terms that the community had already defeated the 11 proposed towers on school grounds and it most definitely did not want a tower in the heart of Chimayó, it was ignored. Jack Eoff, a radio technician and owner of towers, addressed the commission claiming that the amount of electromagnetic radiation emitted by cell phones and towers is miniscule and not harmful to human health. He asked the commissioners to not make a decision based upon what he called "emotional testimony." His appeal obviously ruffled some commission feathers and chairman Elías Coriz responded, "We base our decisions on facts and discovery, not emotion." The commissioners were unanimous in their decision to impose the moratorium while the Planning and Zoning department redrafts an ordinance that will require review of any tower proposed in Rio Arriba County. They all addressed the fact that the placing of this new tower in a residential and cultural area of Chimayó was completely inappropriate, but also acknowledged they had concerns about health issues. Commissioner Coriz added, "The ordinance as it stands now gives carte blanche to corporate America." Once again, community members who quickly organized, did their research, and presented their case were effective in getting the response they wanted from a government agency. In the case of the battle against the proposed cell phone towers on school grounds in the Española Valley, the process took a total of three weeks: notices appeared on fences alerting the public to a Planning and Zoning meeting to consider a request from the telecommunications company to erect the towers; a core group of community activists formed the Council on Wireless Technology and held a community-wide meeting that was attended by teachers, kids, lowriders, Democrats for Progress, and many members of the Holy Family congregation; school board member Ralph Me-dina moved to cancel the contract and the board unanimously backed him up. The current charge took less than two months from the time the tower appeared on the hill above the heart of Chimayó to a unanimous county commission decision. The process is not over, of course, until the Chimayó tower is taken off-line (it was activated the weekend of April 8) and finally, dismantled. But through due diligence, the Council managed to discover two procedural mistakes, on the part of the county and T-Mobile, that may result in an injunction against the tower. The Department of Cultural Affairs Historic Preservation Division, after being contacted by community members, has informed T-Mobile that it failed to provide adequate documentation that there were no historic properties affected by the celluar tower and that the company must re-submit a consultation "packet" with accurate photos and maps. In the meantime, an Historic Preservation officer is visiting the site to ascertain the distance of the tower from the Chimayó Plaza and El Santuario, which are both listed as historical properties. As for the County, apparently the Planning and Zoning Department based its approval of the tower on an outdated 1995-1996 ordinance instead of a 2000 ordinance that requires that towers not more than 70 feet in height go through a review process by the County Commission. Towers above 70 feet are prohibited. The Commission only recently became aware of the 2000 ordinance that apparently supersedes the 1995 ordinance and must work with the county attorney to determine how it will rectify the mistake. If this was due to incompetance on the part the Planning Department, or a case of "selectively enforcing" an ordinance, an accusation that previously has been leveled, then the county is vulnerable to legal action if it moves forward with an injunction against the tower. Hopefully, all the good work of the Council will ensure the good-faith efforts of the Commission to redraft an up-to-date ordiance and see that it is enforced. ANNOUNCEMENTSNorthern Arizona University researchers want to talk to you! We are looking for 25 people to discuss their opinions about forest management and restoration. Participants will get paid cash for their opinions, plus receive an all expenses paid weekend to participate in a three-day citizen's panel in Taos during October 2006. No special knowledge is needed. Your interest in these issues and willingness to tell us your opinions is all that matters. Call toll-free now to get more information: 1-866-213-5716. Additional information can be found on the Internet at www.nau.edu/nmpanel. We're waiting to hear from you! The Taos Valley Abeyta adjudication proposed settlement was finally released to the public on March 31. Originally filed in 1969, the adjudication suit governs Taos Pueblo's water use and its claims against the town of Taos, the Taos Valley Acequia Association (55 acequias), El Prado Water and Sanitation District, and 12 domestic water users associations. Unlike the Aamodt adjudication proposed settlement, negotiators of the Abeyta are calling it a "community driven" agreement that maintains the status quo of water use in the Valley. Most importantly, the agreement protects the Valley's 55 acequias and delineates their water allotments consistent with long-standing custom. The Pueblo has agreed to irrigate only one-half of its 5,712 irrigable acres for now, so as not to impact non-Indian water users. Like the Aamodt, however, there are major factors in the proposal that are contingent on future decisions and realities. Taos Pueblo will be allocated 2,440 acre-feet per year (afy) of San Juan/ Chama Project water; the town of Taos will get 500 afy (in return for limiting some of its wells) and El Prado Water and Sanitation District will get 50 afy of Project water. This is all on paper at this point, as there is no diversion facility and the amount of available imported water is subject to drought conditions. The federal price tag for the settlement is $100 million dollars: $20 million for water rights acquisition; $54.45 million for water infrastructure programs; $1 million for the Pueblo's Buffalo Pasture recharge project; $5 million to fund administration; and $19.55 million for tribal council approved programs. Governor Bill Richardson vetoed the state's commitment of $75 million to settle Indian water rights claims, and the federal government has reneged on its financial commitment to the Aamodt settlement. It remains to be seen what kind of funding will be available. La Jicarita News will provide a detailed analysis of the proposed Abeyta settlement in the May issue of the paper. Editorial: Is the Forest Service Prepared?By Kay MatthewsIn the May/June 2004 issue of La Jicarita News I told the sad story of my neighbors' struggle to register their firefighting bus business on the official government website that requires all contractors &endash; no matter how large or small &endash; to buy into their bureaucracy. Now, two years later, both contractors are going out of business, as are most of the other bus drivers in the area. Why? Because, in this year of severe drought, the worst in a century, there are no firefighters to drive. The Carson National Forest announced that it will not be fielding any Type II Swift crews this year, meaning the local people who work seasonally as firefighters in Peñasco, Questa, El Rito and Taos. The forest will use only the Type I Hot Shot crews (they have their own Forest Service vans), who are permanent forest crews, and contract crews, from the Carson and Santa Fe forests, and if need be, from Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, etc. The official reason for this is, according to the forest spokesperson, that the forest has been unable to recruit enough seasonal employees for these types of crews over the past few years and are not even going to try this year. She admitted that there have been some administrative problems as well, and the Forest Service is going to look into how to improve the situation. The unofficial reason that runs through the rumor mill is that the crews are too much trouble to deal with, both because of unreliability on the part of the crews and too much paper work for the local Forest Service. Those firefighters who want to work as contractors will have to go through the ordeal my bus driver friends did to register their businesses nationally. My neighbors were never officially notified that there weren't going to be any Swift crews hired this year. The first they heard about it was from me, and I read about it in The Taos News. Fortunately, they hadn't already bought insurance for the season and they subsequently made the hard decision to get out of the business. No Swift crews were hired last year, either, and the drivers were never once called; Hot Shot crews from all over the west were deployed instead. Tomás has been driving fire fighting crews since 1970; his son Fred, since 1998. Over the years they have invested considerable money in their buses, their training, and the rising cost of insurance. Several weeks after the article appeared in The Taos News there was a letter to the editor from a crew leader in Taos who claimed that for the past few years he has successfully recruited a team of local fire fighters, contradicting the Forest Service excuse that there aren't enough seasonal people to fill the crews. I suspect that above and beyond the forest's official rationale its decision is part of a larger pattern that continues to centralize personnel and services in all facets of Forest Service management: firefighting crews, professional positions like wildlife biologists and archeologists, and NEPA specialists (many of the EIS's that are released for projects in New Mexico are actually written by an out of state team). It used to be that the two main employers in our small northern New Mexico communities were the public schools and the Forest Service. That may not be true anymore. The Forest Service spokesperson told me, "We get nostalgic about the way it used to be but it's not going to be that way anymore." When I worked as a seasonal employee of the Forest Service back in the 1970s and 80s we had a strong presence in the community. And by we, I mean the seasonal hires: fire patrols who drove designated routes talking with folks in the woods about fire danger or wood gathering; hiking patrols who talked with hikers and backpackers about where to camp and what routes to take; standby firefighters who were fixing fence, repairing trails, or picking up trash; YCC kids working on rehabilitation projects; fire lookouts who entertained visitors up in their isolated towers above the forest canopy; and Smokey Bear and Woodsy Owl in local classrooms talking with kids about forest protocol. While we may object to some of the false testimony Smokey was dishing out about stamping out all forest fires (we now live with the results of overgrown, small-diameter forests that are doubly susceptible to fire), at least the Forest Service had a presence in the community that derived from the community. Now, the only faces we see are the district rangers and forest supervisors on their way up the bureaucratic ladder, and about the only time we see them is when we're negotiating the appeal of a lousy EIS. Back in the 1990s Camino Real District Ranger Crockett Dumas was a frequent visitor to people's houses, to Los Siete in Truchas where community members gathered to hash out problems on the district, at the local thinning sites where folks cut their firewood, or on his horse high up in the Santa Barbara checking out grazing conditions. Those kinds of employees are not particularly welcomed in the Forest Service. The agency doesn't want its staff getting too chummy with the folks they ostensibly serve. It's not through "horseback diplomacy" that the Forest Service is trying to assert its authority in northern New Mexico; it's by one size fits all professional management. There doesn't seem to be much pretext left that northern New Mexico is a unique area of the country that requires a unique and locally aware work force largely comprised of the folks who actually live here. Theoretically, that may ultimately be for the best: the Forest Service is, as Ike DeVargas identified it, the occupier. But economically it's a hardship for folks like my neighbors and all of us who spent a lot of years out on the ground trying to do get some good work done.

|

Agriculture Revitalization InitiativeBy Mark Schiller and Kay Matthews (with Paul White and Lynne Velasco)All of us who live in the small, rural communities of northern New Mexico are concerned that lands with water rights not being put to use are in jeopardy of being lost to forfeiture. As more and more of our children leave the communities to find work elsewhere, and as downstream cities look to el norte to procure water rights to facilitate growth and development, we need to take a realistic look at what it's going to take to keep land and water in agricultural use. La Jicarita News has reported extensively on the Aamodt adjudication, especially with regard to the folks who formed the Pojoaque Basin Water Alliance to raise concerns about the proposed settlement. As parciantes and well users in the Pojoaque Basin, they are particularly vulnerable to land development and loss of water rights. There has been at the very least a 50% loss of agricultural lands in the Pojoaque/Nambe basin from the 70s to the early 90s, and the loss continues. Several Alliance board members, Paul White and Lynne Velasco, in conjunction with Tawnya Laveta of the Santa Fe Farmers' Market Institute, have drafted an Agriculture Revitalization Initiative. The proposal seeks to protect land "at risk", which is land that has historically been used for subsistence or entrepreneurial farming and/or ranching and is currently owned by a person or persons who are unable to continue farming or ranching. Consequently, the land is susceptible, after five years of non-use, to loss of historic surface water rights under state forfeiture law. The Agricultural Revitalization Initiative proposes to create a data base to match interested land at risk owners with resources such as "farm/ranch stewards, farm equipment operators, tools and machinery, farm/ranch supplies, labor interns and volunteers." Other services would include farm/ranch mentorship, business planning, distribution and marketing of agricultural products, and technical support for researching and applying for federal, state, local, and foundation funding. In layman's terms, what this means is that existing land owners could get the help they need to turn their farms or ranches into value-added agricultural enterprises, or those land owners who are unable to do the work themselves could be put in touch with farmers and ranchers from within or without their communities who seek to extend their own agricultural businesses. According to the proposal, the Pojoaque Basin is highly susceptible to loss of agricultural lands due to provisions in the Aamodt settlement that allow inactive water rights to lose priority protection. Unused water rights placed in a water bank are also subject to loss of priority protection after five years, withut notice, and will be potentially used by the pueblos, state, county, or city. A pilot project connecting parciantes with resources and/or farming stewards would preserve surface water rights, farmland, maintain the vitality of the community, and help develop regional economic development. Organizers hope that collaborative partnerships can be developed with county extension agencies, the Sustainable Agricultural Field Station in Alcalde run by NMSU, New Mexico Department of Agriculture, New Mexico Organic Commodities Commission, New Mexico Acequia Association, the Interstate Stream Commission, New Mexico Farmers' Marketing Association, local farmers' markets, regional land trusts, Eight Northern Pueblos, Farm to Table, Southwest Marketing Association, small business development centers, Quivira Coalition, and many more. The co-editors of La Jicarita News, as members of the Rio Pueblo/Rio Embudo Watershed Protection Coalition, are interested in working with the initiative on a pilot project in the Pojoaque Basin. We're hoping to organize a meeting of potential stakeholders this spring to develop ideas for a proposal to underwrite the costs of setting up a non-profit clearing house to jumpstart the project. If anyone would like to learn more about the initiative or participate in a meeting, please e-mail Paul White, paulwhite@sisna.com, or Lynne Velasco, lynnenambe@cybermesa.com. Book Review: The Witches of Abiquiu: The Governor, the Priest, the Genízaro Indians and the DevilBy Malcolm Ebright & Rick HendricksReviewed by Kay MatthewsThe Witches of Abiquiu authors Malcolm Ebright and Rick Hendricks tell a mind-boggling tale of witches, sorcery, spells, exorcism, curses, and battles with the Devil during the establishment of the Abiquiu Genízaro land grant between 1756 and 1766. Although it stretches the credulity of the modern reader, this solidly researched and meticulously documented story reveals a time of social conflict and culture clash during one of New Mexico's most interesting historical periods.

During this mid-eighteenth century period, as Spaniards attempted to reestablish their dominance after the Pueblo Revolt (1680), their settlements increasingly came under attack by raiding Comanches, Utes, and Apaches. Abiquiu found itself "in the middle ground between the communities of Santa Fe and Santa Cruz de la Cañada [current day Española and Chimayó]" and the raiding Indians. It was therefore critical that a land grant be established to provide a "bulwark" between the two conflicting peoples. But unlike many of the other land grants that were being established throughout northern New Mexico, Spanish Governor Vélez Cachupín desired to establish an Abiquiu land grant comprised of Genízaros, or as the authors define them, those people with Indian blood who became servants to the Spanish colonists. This definition includes nomadic Indians who lost their tribal identity through captivity and servitude and lived on the margins of Spanish society. Vélez Cachupín believed the Genízaros, who knew the enemy, would be more successful than the Spanish elites who were commonly given land grants. But the middle ground, or nepantla, the Genízaros inhabited, provided fertile ground for the flourishing of witchcraft. Vélez Cachupín's great experiment became his worst nightmare as the Christianization efforts of the Abiquiu priest, Father Juan José Toledo, clashed with the Indian belief systems and played out in witchcraft and devilry. The authors guide the reader through the story by providing an historical context, profiling the main protagonists in the drama, and detailing the four phases of the witchcraft proceedings. Chapters 1 and 2 set the stage for the witchcraft outbreak by providing the history of the Abiquiu area and the Genízaros who settled there. In Chapter 3 we meet one of the most interesting characters in the drama, Father Juan José Toledo. While he endured the entire episode and remained at the pueblo for six years afterward, he is largely responsible for much of the hysteria and confusion that reigned during these years. The son of Spanish immigrants to Mexico, he was raised in Mexico City, became a Franciscan priest, and was assigned a posting in New Mexico. The Franciscans were fervent in their desire to Christianize the Indians, whom they viewed as child-like. Taking up his post at Abiquiu in 1754, after many other positions in New Mexico, Father Toledo found himself at the mercy of a small group of Genízaro sorcerers who attempted to challenge his authority. They worked their "sympathetic magic", or poison and herbs that cause illness, not only on Toledo but upon each other as a means of settling their disputes. Toledo's interpretation of all this came under the theologically accepted rubric of a Pact with the Devil. Once Toledo filed a report with the Spanish governor (Marin del Valle, who was governor between Vélez Cachupín's two terms) an investigation began that broadened to include every suspected sorcerer and witch in Abiquiu and beyond. The authors detail an amazing list of these sorcerers: El Cojo (the Cripple), who supposedly ran the School of the Devil; El Viejo, the most powerful sorcerer; Vicente Trujillo and his wife Maria, who were responsible for many deaths and illnesses; and El Descubridor, the chief informer. The proceedings evolved from an investigation of these sorcerers to an outbreak of demonic possessions and exorcisms, which Father Toledo conducted in an attempt to wrestle control from the Devil. It fell to the other story protagonist, Vélez Cachu-pín, to deal with the deteriorating situation at the pueblo. Cast in a sympathetic light, Vélez Cachupín is seen as one of the more enlightened Spanish colonial governors who was able to resolve the conflict without the drastic measures often employed by the Inquisition (although he did tie Maria Trujillo to a wagon wheel until she confessed). Vélez Cachupín is credited with establishing some of the enduring land grant communities such as las Trampas, Truchas, and Abiquiu. And the authors believe that it was largely due to his understanding of Genízaros, Pueblos, and the nomadic tribes, that there was a cessation of raids on Spanish settlements. You'll have to read the book to see how he dealt with the illness, accusation, injustice, and conflict that marked the witchcraft proceedings. In the Conclusion and Epilogue, the authors summarize their analysis of what happened at Abiquiu. While there was a general belief in witchcraft among both the Spaniards and the Indians, the Spaniards believed that the curanderos, or healers, only practiced hechería, or witchcraft. As the authors explain, "At the heart of the Abiquiu witchcraft trials is the problem of distinguishing between witchcraft practices that were malevolent, healing practices that were beneficent, and other techniques such as love magic that were somewhere in between." But the Abiquiu Pueblo survived, and the Genízaros became Hispanicized as full-fledged citizens of New Mexico. The Abiquiu land grant was confirmed in 1894 and the "Residents of Abiquiu still retain the Hispano-Pueblo duality that is their strength."

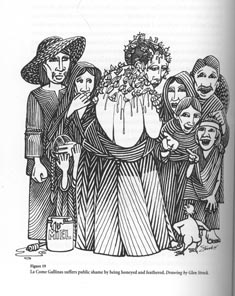

Dramatic woodcut drawings by Glen Strock accompany the text and provide a colorful cover. The first hardback edition published by the University of New Mexico Press is sold out. Hopefully, the press will soon reprint in both hard and soft cover: this is a book that should be in every public school and institution in New Mexico and be available to the general reading public at an affordable price. Camino Real Gets New District RangerBy Mark SchillerWhile the Camino Real Ranger District of Carson National Forest has a new district ranger, John Miera, he is not new to the position: Miera was district ranger on the Española District for seven years and before that on the Coyote District for three years. He experienced much of the turmoil and conflict among the Forest Service, forest-dependent communities, and environmentalists that dominated those years. La Jicarita News and community forester Max Córdova recently went in to visit Miera. The primary issue that's on everybody's mind is the effects of the on-going drought on forest management. Miera told us they are evaluating fire danger on the district by identifying needs and applying for "fire severity funding" to bring in added resources and personnel they anticipate will be necessary to protect the area. He acknowledged that this district is particularly dependent on forest resources for heating, cooking, and construction and encouraged residents to think about doing their woodcutting in the spring, as he anticipates the forest may impose fire restrictions that would preclude that activity. Miera also said that he and Melvin Herrera, district range manager, had met with the majority of grazing associations on the district and that the permittees had voluntarily chosen to reduce the number of livestock they are going to put on their allotments. He estimated that the associations would utilize 70-80 per cent of their permits. Miera told us that he already met with several acequias to talk about Forest Service policy regarding access across Forest Service land for ditch maintenance and rehabilitation. He maintained that parciantes must apply for and receive special use permits for any activity that he termed "ground disturbing." This would include projects in which heavy equipment or access by motor vehicles is necessary. This has been an on-going issue between the Forest Service and parciantes who maintain their ditches predate Forest Service tenure and their access is guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Finally, we asked Miera if he would consider reinstituting "ranger days", so that community members are able to comment on current or potential projects. "Ranger days" was a successful part of Collaborative Stewardship during Crockett Dumas' tenure but was discontinued when he left the district. Commenting on community concerns about the high turn-over of Forest Service personnel affecting the continuity of projects, Miera said that as a native Taoseño he had no aspirations to leave the area and hoped he would be on the Camino Real for quite some time.

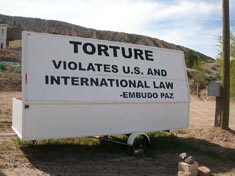

Billboard in Rinconada sponsered by the peace group Embudo Paz: it is the second of a planned series of political messages leading up to the election in November.

|

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2002 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.