|

|

|

Volume V |

August 2000 |

Number VII |

|

|

Embudo Valley Community Supported Agriculture: A Community Garden for Dixon/Embudo By Mark Schiller and Kay MatthewsANNOUNCEMENTSTruchas Montaña Youth Team Tours Los Alamos Burn By Max Cordova, Jr.Taos Soil & Water Conservation District Annual Tour By Kay Matthews |

Puntos de Vista: EN EL NOMBRE DE DIOS TODOPODEROSO ¿QUE HA PASADO CON EL TRATADO? By Georgia Roybal, with input from Roberto Mondragón-Anton Chico Land Grant, Estevan Arellano-Embudo Land Grant, and Juan Sánchez-Chililí Land Grant Churro Cavorts Again By Georgia SpelvinEditorial By Kay Matthews and Mark Schiller |

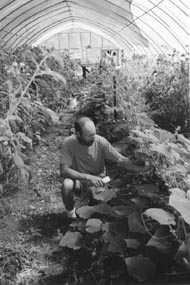

Embudo Valley Community Supported Agriculture: A Community Garden for Dixon/EmbudoBy Mark Schiller and Kay MatthewsTwenty-two households are currently enjoying an abundance and variety of vegetables from the Embudo Valley Community Supported Agriculture (EVCSA) project: lettuce, chard, arrugala, tomatoes, herbs, carrots, turnips, garlic, cabbage, and squash, to name a few. The families paid $375 last spring for 26 weeks worth of produce, which will continue until the first week of November.

EVCSA is the project of three farmers: Linda Prim, Felicite Conseca, and Bob Pederson. They farm on three parcels of land, with a greenhouse and "hoophouse", and sell the produce at the Santa Fe Farmers' Market as well. Prim wears several other hats as the editor of the Farm Connection, a newsletter that serves as an information exchange for New Mexico farmers, and as an inspector for the New Mexico Organic Commodity Commission. Felicite Conseca is manager of the Española Farmers' Market and is described by her partners as the "Harvest Queen", the garden workhorse. Bob Pederson is a season extension specialist who is working on a system to heat the greenhouse with solar hot water so that the farmers can grow throughout the year.  The concept of Community Supported Agriculture, the farmers told us over a delicious lunch of their organic vegetables, began in Germany and Japan. The goal is to involve as many people from the community as possible in local agriculture and make organic food available at affordable prices. CSAs provide advantages to both farmers and consumers: the farmers gets money up front in the spring to defray the planting and start-up costs and have a reliable market; consumers get 25% off the farmers' market price, and neither the farmer nor the consumer has to drive to town. The farmers also pointed out that CSA shareholders also become much more aware of where and how their food is supplied, as they share in the the vagaries of farm life's abundance and scarcity. While the majority of shareholders pay for their produce, the EVCSA also offers worker-shares: four hours a week equals a 50% reduction in share price. Linda Thomas is participating in the project as a worker-apprentice to learn about farming techniques and to satisfy her desire for organic produce.

Shareholders are provided produce once a week, which changes with the growing season. In May and June they get salad mix, lettuce, spinach, scallions, peas, radishes, turnips, parsley, broccoli, raab, arrugala, and swiss chard. In July and August they continue to get salad makings and carrots, beets, summer squash, zucchini, basil, cucumbers, green beans, cabbage, tomatoes, garlic, and onions. In September to the first frost the produce includes everything from July and August as well as chile, potatoes, sweet peppers, leeks, winter squash, and radicchio. Shareholders can also buy eggs, goat cheese, goat milk, goat yogurt, and organic chicken, supplied by other New Mexico organic producers. EVCSA publishes a weekly newsletter of information about what kind of produce is available, what to expect in the coming weeks, and recipes to help cook up all that is provided. Deborah Madison, a nationally known chef and vegetarian cookbook writer who lives in New Mexico, has graciously allowed the farmers to use recipes from her cookbooks. All three farmers are dedicated to non-exploitative, sustainable agriculture in the Embudo Valley. They recognize that community participation is vital to maintaining the long tradition of small-scale agriculture in the Southwest. They hope that the EVCSA will serve as a model for other agricultural enterprises and as an educational tool for area youth: Embudo neighbor Estevan Arellano already brought the Youth Conservation Corps to visit the farm this summer. Felicite, Bob, and Linda are also particularly pleased that the WIC program, which provides food to low-income families with children, has initiated a voucher systems that allows participants to buy at farmers' markets. They point out that surveys demonstrate once these people are exposed to local produce they continue to buy at farmers' markets when they are no longer on the program. They hope that CSAs can keep the costs of organic food affordable. The Embudo Valley CSA is looking to expand the number of shareholders for next year to 45 to 60. Anyone interested (they will accept customers from the Taos and Peñasco areas as well) in participating can contact Felicite Fonseca at 579-4085. ANNOUNCEMENTSWater and Acequias! The New Mexico Acequia Association is sponsoring a workshop for Peñasco area acequia comisionados, mayordomos and parciantes to come together to listen and talk about how best to keep their acequias vital and their water rights intact. Representatives from other area acequia associations, such as the Taos Valley Acequia Association and the Dixon/Embudo Acequia Association, will be on hand to share information on their associations, how and why they organized, and what they are doing to maintain and protect their acequias. Date: Saturday, August 26, 2000 Time: 1-4 pm Place: Peñasco Centro de Comunidades (on State Highway 75 in Peñasco) Truchas Montaña Youth Team Tours Los Alamos BurnBy Max Cordova, Jr.Montaña de Truchas Youth Team had the opportunity to go with forest employee Daniel Mondragon of Santa Fe National Forest on July 1 to look at, evaluate, and monitor the effects of the Cerro Grande fire. As we drove through acres and acres of burned forest it was overwhelming to see the devastation of the fire and its impact on the forest. One could still breath smoke and ash several weeks after the fire occurred. With the few rains that have occurred in the area, ash and soot have escaped into the arroyos and gullies and it seemed as if they were paved with asphalt. Every time trucks passed these arroyos huge clouds of ash and dust leaped into the air. The first thing we looked for was some sign of wildlife. There were no birds, no chipmunks, no signs of any wild animal. A fire of this magnitude definitely has an impact on wildlife. The only signs we found were in isolated forested areas that survived the fire because they had been thinned as fuelwood areas the communities. We then evaluated what was growing after the fire. Although it was impressive to see the green leaves of scrub oak sticking out of the ground blackened with ash and soot, it was sad to see piñon and pine forest replaced with scrub oak. There is little value that people in the community see from scrub oak. For animals it provides some forage and nuts every third or fourth year. It is a prolific plant that sucks a lot of water from the ground and is hard to thin and burn. Sheep and goats like it but where are these herds now? Nowhere to be found. The Forest Service was planting grass seeds on the land. The tiny seeds were very noticeable on the black background. It is our opinion that these seeds will probably all wind up in arroyos and the Rio Grande because the ash present on the ground is very unstable. It would probably have been better if the Forest Service had waited for some rains to come and allowed time for the ground to stabilize. The fire burned several inches into the ground. There is evidence that a lot of acres were sterilized by the fire. We put monitoring points on these areas to evaluate the impact of the fire at different times during the year. We observed no difference in areas of pine and piñon/juniper where the wind-driven fire passed; the devastation was enormous in both kinds of forest. The Forest Service is hoping to salvage some of the trees, although in the past this has created a lot of controversy. There are many pros and cons on the issue of salvage logging. The Forest Service asked if we felt the communities would want this wood. It looked like very dirty work to us. It is important to provide wood to the communities before a fire occurs, not after. As we noted earlier, the only areas that survived the fire were those that had been thinned. In one area we saw that the trees had just been felled by the Forest Service and lay scattered on top of each other on the ground. This simple task saved many trees from being burned. It demonstrated that communities are on the right track in working with the Forest Service on thinning projects. Fire as a tool in restoring forest heath is a quick way to thin forests but by itself it certainly isn't the best way. We spoke to several groups who think that the Forest Service should first thin forest areas before it considers a prescribed burn. Special thanks to District Ranger John Miera for his help. Taos Soil & Water Conservation District Annual TourBy Kay MatthewsThe Taos Soil & Water Conservation District (TSWCD) tour of acequia rehabilitation and flood control projects in the Peñasco area was testimony to the dedication and hard work of local acequia commisioners and mayordomos. As we toured the various projects, from Vadito to El Valle, it was obvious that without their perseverance and commitment to maintaining their acequias, many of these two and three hundred-year-old ditches would have already fallen into disrepair. The TSWCD Annual Tour was led by staff member Peter Vigil, along with board members from the Taos area, including Celestino Romero, Maureen Johnson (president), Felix Santistevan, and Edward Grant. Acequias were represented by Pat Lopez and Arthur Pacheco of Peñasco; Alfredo Dominguez (also a TSWCD board member) of Chamisal; Rudy Pacheco, Mike Pacheco, and Edward Leyba of Rio Lucio; Conrad Romero of Rodarte, Roxanne Varela of Questa, and myself, from El Valle. The first sites the group visited were streambank protection projects in Vadito and Rio Lucio. The TSWCD provides cost share funding (85%) and technical assistance in three areas: flood control; range improvement; and acequias. These streambank projects, as part of the flood control assistance, usually consist of a combination of gabion baskets and vegetation that help prevent erosion by stabilizing the soil along the riverbank. As Peter Vigil explained, flood control is not an exact science, and the monitoring of these projects is an important part of his job. Projects can be reviewed and evaluated to improve services and ensure wise use of funding on other projects. A picnic lunch was held at Hodges Campground, where tour members looked at the Chamisal/Ojito diversion, a simple concrete structure which has deteriorated over the years and is a priority for rehabilitation. The group then traveled up the road from Hodges towards Llano and climbed the steep embankment to the Chamisal/Ojito culvert project. Here, where the acequia flows through a narrow channel in the side of the embankment, rain consistently blew out the side of the ditch. As part of a three-part project, TSWCD provided funding for a four-foot culvert to prevent the erosion of the acequia. Members of the Acequias de Chamisal y Ojito provided 11 days of labor. A second culvert was installed at the confluence of the Rio Chiquito and Chamisal/Ojito acequia, along with gabion baskets and a cow crossing, which everyone agreed was a good idea. In Peñasco the group visited the Acequia Madre de Peñasco, where a new weir divides the ditch into two acequias. TSWCD provided cost-share funding of $1,100 for the cost of the weir, which was fabricated locally. The next stop was the Rio Lucio Southside Acequia project (right on SH 76 near the junction of SH 75), a presa rehabilitation for which TSWCD contributed 5% of the $45,000 costs. Here, a very sophisticated concrete diversion was built to withstand flooding. In their assessment of the project, however, acequia parciantes requested that the headgate be lowered to better facilitate irrigation. The last stop was El Valle, where the group visited the Acequia Arriba de El Valle, another large rehabilitation project where many sections of culvert were placed in the acequia to prevent water loss. TSWCD contributed $3,500 to the design cost of the project, which was incurred by a private engineer, who was hired to expedite the project (The Natural Resources Conservation Service, which normally provides design work through the Office of the State Engineer's cost-share program, was unable to provide a design in a timely fashion). The Acequia Arriba is in a difficult area for rehabilition: The presa sits in a steep canyon above the village and the ditch travels through rock barriers and narrow channels to the village fields. The acequia commissioners chose to line the acequia with culvert to conserve water in the more accessible areas below the presa. The TSWCD is accepting applications for any of its three areas of funding until August 31 in its Taos Office .

|

Puntos de Vista: EN EL NOMBRE DE DIOS TODOPODEROSO ¿QUE HA PASADO CON EL TRATADO?By Georgia Roybal, with input from Roberto Mondragón-Anton Chico Land Grant, Estevan Arellano-Embudo Land Grant, and Juan Sánchez-Chililí Land GrantEditor's Note: This Puntos de Vista initiates a new feature of La Jicarita News that will focus on the history and status of some of el norte's land grants. In 1598 Don Juan de Oñate came from Mexico to settle New Mexico for Spain. He brought with him Spanish, Mexicans, Indians, mestizos, and Spanish land use and ownership practices. In 1680, the Pueblos threw the Spanish out of New Mexico. Twelve years later, Don Diego de Vargas led the reconquest. Then began the establishment of the land grants under the King of Spain. The Laws of the Indies of 1681 codified the land use practices as to where to set up their communities, how to design them, how to govern them, and how to keep them economically sustainable. To establish a land grant, a group of people or an individual petitioned the governor. The petition declared that the area was not occupied and described its location. A local official investigated the request. He made a map and a report signed by two witnesses. He then submitted the paperwork to the governor and the governor granted title. Recipients had to live and work on the land for 4 years to secure the title. Also, if they had land in one grant they could not apply for land in another grant. The land grants given to groups assigned plots of land (suertes) to individual families and used large sections of land communally for grazing, called dehesas. The montes were for woodcutting or harvesting wild fruits. These were called the common lands. In 1821 Mexico gained its independence from Spain and followed the same procedures and practices for establishing land grants. The one difference was that, since Mexico wanted to populate its northern frontier, grants could now be made to outsiders if they became Mexican citizens. In 1846 the U.S.-Mexican War began. The United States invaded all the way to Mexico City. General Stephen Kearny came to Las Vegas, New Mexico, in 1846 and promised to harm "not a pepper, not an onion." There were rebellions against the U.S. in Santa Cruz de la Cañada, Embudo, Mora, and Taos in 1847. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. This treaty ceded over half of what was then Mexico to the United States. Article 8 guaranteed "property of every kind . . . shall be inviolably respected." Article 10 stated that all grants of land would be respected as valid as if they had remained in Mexico. The U.S. threw out Article 10. Mexico forced the negotiation of the Protocol of Querétaro which stated that the American government by suppressing Article 10 "did not in any way intend to annul the grants of lands" and that "legitimate titles . . . are those which were legitimate titles under the Mexican law." Then the fraud, collusion, and chicanery began. Hearings on titles were conducted in English. Notices were published in English in papers far away from the site of the hearing. Incorrect translations of Spanish were used. The Spanish title descriptions were of physical features, such as mesas, cordilleras, arroyos, etc, not township and range as in the English system. Communal property ownership was not recognized by English law. In Spanish legal practice customary law was as important as statutory law. (This was a result of much of the empire being far away and thus the people having to set rules or customs for their areas.) English law did not recognize the importance of customary law. Legislators made laws changing land grant boundaries to enable friends to gain control of property. Lawyers were paid one-third of the entire acreage in a land grant to defend the land grant even for small acreages. Legislators then passed laws that allowed any single landowner (including the lawyers) to demand sale of the common lands or to distribute them equally to all owners. The federal employees in charge of surveying and judging the boundaries often awarded themselves large tracts of land. People were misled into signing documents (many were illiterate and signed only with an x) which, unbeknownst to them, transferred title to the land. Officials declared that land grants which were owned by a group were really owned by one person and then that person (often a político) was coerced into selling or turning over that land. The state also decided that the land grants were subject to taxation. The Pueblos, however, which were also recognized as land grants, were not taxed. Under Mexican law Pueblo and Spanish grants were treated the same. The heirs to the land grants had no idea that taxes were due until an official showed up and told them that they had lost land due to non-payment of taxes. Some land grants were formed into corpora-tions whose boards then sold the lands. Much of the land lost is now under the control of federal government agencies. All of this has caused great resentment and occasional violence. In 1967, Reyes Lopez Tijerina and his followers took over the Rio Arriba County Courthouse in Tierra Amarilla. In 1989, several people occupied land just south of Tierra Amarilla in defiance of a court order. Two hundred acres were finally awarded to a village concilio, primarily on an issue of due process rights violation. In 1995, the New Mexico Land Grant Forum was formed. The purpose of the Forum was to recruit elected officials or heirs to a land grant and other interested parties to meet, discuss issues of land grants, and to advocate for the preservation and possible restitution of land grants. Federal legislation calling for a commission to re-adjudicate the land grants by heirs petitioning the commission was first introduced by Bill Richardson. Similar bills have been introduced by Bill Redmond (his passed the House of Representatives), Jeff Bingaman, Pete Domenici, and Tom Udall. Meanwhile, Senators Bingaman and Domenici have requested a three-year study by the General Accounting Office. That study has now begun under the direction of Richard Kasdan. That study should, in part, pinpoint failings by the federal government and make suggestions for restitution by December, 2002. At the state level, the New Mexico Land Grant Forum is currently in the process of reviewing state statutes regarding land grants and re-defining their rights and responsibilities. A state task force has been formed under the direction of the Attorney General's office to assist the General Accounting Office investigation. Another effort of the New Mexico Land Grant Forum is that of collaboration with universities for a university level land grant curriculum. The board of Luna Vocational Technical Institute has unanimously approved establishing a cultural study center which will include archiving land grant records. Dr. Felipe Gonzales of UNM has funded two research assistants and is also recommending a possible second study center at UNM. One on-going project is a publication that will include chapters written by individual land grants about their history with the help of research assistants. Discussions have also taken place with the Law School at UNM to provide students for doing research under the guidance of Professor Em Hall. The New Mexico Land Grant Forum continues to support a re-adjudication process. Under this process, heirs to any grant (active or defunct) can petition for a re-adjudication. The remedies suggested by the Land Grant Forum have never included money. The restitution they have requested is money to buy property that once was part of the grant. If the present owners do not want to sell, the Forum has requested that similar acreages of federal land be returned to the land grant. En el nombre de Dios todopoderoso, ¡sí se puede! Churro Cavorts AgainBy Georgia SpelvinSpider woman, in her shimmery gown, spins her silvery web, weaving the world. Up pops one of her most winsome creatures, a perky little sheep with sparling eyes, a very active pink felt tongue and a polka-dot bow in her hair&emdash;er, pelt. This is no sheep anyone ever herded out on the range, but a delightful puppet. Churro is the star of a puppet-and-dancer musical bearing her name. During the course of the delightful 45 minute musical Churro meets many other puppets. These include a grumbly Human; Señor Merino, a dashing Hidalgo noblesheep; Monsieur le Comte de Rambouillet, a gallant French nobelsheep disguised as a voyageur; a Rio Grande girl in colonial era garb; and a Navajo girl in velvet jacket and ruffled skirt. "I love adventure And I love to see What's over the next hill For me . . ." sings the winsome puppet in her distinctly puppety voice as she retraces the history of her breed of sheep. From her probable origin in the mountains of Central Asia, into the Fertile Crescent, to Spain, to Mexico (via a cardboard ship on which she is thoroughly sick) and thence up to northern New Mexico, Churro is a sheep with a taste for kicking up her hooves. All this was the creation of composer-playwright-puppeteer Joanne Forman, who has lived in Taos for 22 years. As she began reading up on the history of the region she became more and more interested in the entwined history of weaving and sheep, and especially in the Churro, nearly extinct by the mid-20th century. The Mountain and Valley Wool Association, sponsor of the very popular Taos Wool Fair, is one of the organizations concerned with restoring and promoting the Churro breed. When Forman came up with her ingenious puppet musical, the fair invited her to be part of the fun. In a candy-striped tent, via story and song, the antics of the puppets and the skills of the performers (including an "orchestra" of three musicians) provides hundreds of fair visitors with entertainment&emdash;and history. "I do love a good problem," admits Forman, "and it was a challenge to make the show fun and also make the important historical and educational points." Audiences could follow the Churro cross with Merino and Rambouillet, the voyage to the New World, her flourishing during the great days of the Rio Grande weaving trade, her meeting with the Navajo, and her decline in the later 19th century, when her wool was deemed unprofitable for machine production. There was even a song detailing the plants used to make vegetable dyes, and a song reminding us to thank nature and the weaver for the unique clothing, blankets and rugs. After two seasons, funding ran out, and Forman went on to other musical projects, including a musical, an opera, an oratorio, a ballet, numerous song cycles and chamber music works. Now she no longer performs as a puppeteer, but her love for the ancient craft remains. Earlier this year she and two friends established Taos Puppet Day, which drew such enthusiastic response that it will become an annual event on the last Saturday of April. "I may not be performing any longer," says Forman, "but that doesn't mean Churro can't." She is eager to put the script and musical score back into circulation, and to assist those who might want to perform the musical themselves. "I do tend to think everyone should be making puppets," she grins, "though of course Churro could be done with humans, or a combination of humans and puppets. It's a great project for school, church or community groups, such as Scouts, 4-H, FFA." For more information, please contact Joanne Forman at (505) 751-1102, 7115 Hwy 518, Ranchos de Taos, NM 87557. EditorialBy Kay Matthews and Mark SchillerJust as our lands are parched and stressed in this time of drought, so too are our tempers as we struggle to find an equitable way to share our diminishing waters. We hear about all the squabbles among parciantes and between acequias as mayordomos try to figure out how to get the water to the last garden, orchard, or pasture on the ditch. Now is the time to end those squabbles, however, or outside entities vying for control of our water will step in and end them for us. The State Engineer Water Master is already turning off water to low priority acequias on the Rio Chama to comply with the adjudication. If this were to happen in our own as yet unadjudicated Rio Pueblo/Rio Embudo watershed, upper valley parciantes would have to stand by and watch the water flow unimpeded to the senior downstream water users at Picuris and Dixon and Embudo. As it stands now, in this time of drought, our downstream neighbors are without sufficient water for their crops. Traditionally, parciantes have always given priority to vegetable gardens, then orchards, and finally pastures. The highest concentration of small-scale farms in the state is located in the Dixon/Embudo valley. These peoples' livelihoods are now in jeopardy. Dr. José Rivera, in his book Acequia Culture says acequias are the birthplace of community and that acequia commissions are the oldest form of democracy in the United States. Farmers, ranchers, and fruit growers must uphold this tradition and work together to determine a fair division of water rather than take advantage of their position on the river. These decisions should be made locally, between individual acequias, or in associations like the Taos Valley Acequia Association and the newly formed Dixon/Embudo association. As Rivera points out, these are the only democratic institutions in many of our villages. We must be careful, however, that acequia meetings not be used as forums to play out personal vendettas or long-standing feuds. The New Mexico Acequia Association will be holding a workshop in Peñasco on August 26 (see page 2) to address acequia issues. This is the perfect opportunity for parciantes to come together to talk about how best to share and protect our most precious resource. If predictions are correct, we may be looking at many years of water shortages. We must act now to plan for that future. |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2000 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.