|

|

|

Volume V |

February 2000 |

Number II |

|

|

Keeping Land Productive: A Profile of Farmers in the Embudo Valley By Kay Matthews ANNOUNCEMENTSThe U.S. Forest Service at a Crossroads By Dan Quinn |

Acequia Water Issues Before the 2000 State Legislative Session By Kay Matthews Editorial By Mark Schiller Tom Udall Comes to Town |

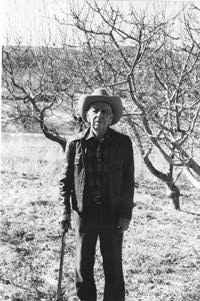

Keeping Land Productive: A Profile of Farmers in the Embudo ValleyBy Kay MatthewsAccording to figures provided by the Rio Arriba County Planning Department, there are over 800 acres of cultivated land in the Dixon area. How many of those cultivated acres produce hay or corn or tomatoes is anyone's guess, but according to Lynda Prim of the Farm Connection in Dixon, more and more farmers are joining together to help one another diversify their crops, process their products, and create markets. Prim publishes the Farm Connection newsletter, which serves as an information exchange for New Mexico farmers, and grows herbs on her own farm in Dixon. Delfin and Fred Martinez own the largest commercial orchard in the Dixon area. In 1950, Delfin purchased his uncle's orchard in Cañoncito and began planting ten varieties of new trees, including red delicious, golden delicious, roman, jonathan, winesap, granny smith, fuji and gala. According to his son Fred, who now runs the orchard for his 82-year old father (who was active until just last year when he was injured in a car accident), "our new strain of red delicious apple makes the old varieties look like Model-Ts." Delfin Martinez With the acquisition of additional acres over the years, the family now has 3,500 trees. The orchard is watered from the Martinez Acequia, the first diversion from the Rio Embudo as it emerges from the box canyon. A huge fan above the trees serves to circulate warmer air when an alarm warns Fred that descending temperatures may harm the tree buds. During harvest, Fred takes time off from his job in Los Alamos, and the entire Martinez clan helps pick and sort apples, along with parttime employees. The Martinez' own their own packing shed, and the apples are sold anywhere and everywhere: straight off the farm, at farmers' markets, in bulk to produce houses both in and out of state, and to New Mexico grocery stores. They also sell cider and the chile and corn they intercrop between rows of young, smaller variety trees. Fred is now close to retirement and soon will be able to work fulltime on the farm. He hopes that his son, who already shares a lot of the farm work, will keep the orchard intact and carry on the family tradition. Clovis Romero and Harvey Frauenglass own neighboring orchards and are fellow comisionados on the Acequia Junta y Cienega in Embudo. Clovis's orchard of 300 trees includes apples, pears, peaches, apricots, and cherries and has been in his family for several generations. His immaculately pruned and cared for trees produce abundant crops that he sells to private customers, at the Santa Fe Farmers' Market, and at the Albuquerque flea market. Like Fred Martinez, Clovis hopes that his son, who also regularly helps his father, will keep the family tradition alive . Harvey sells his fruit at the Santa Fe Farmer's Market as well, but his main product is Big Willow cider, which he makes with his press on the farm and markets in Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Taos. He and his wife, artist Gayle Fulwyler Smith, moved to the farm in 1973. The house they live in was originally the home of Father Cooper, the local priest, who died in 1958. Both Clovis and Harvey are members of the Rio Pueblo/Rio Embudo Watershed Protection Coalition, which is an advocate for the vitality of acequias and agricultural land. Their neighbor, Estevan Arellano, is also a farmer and an heir to the Embudo Land Grant. Almost every square inch of his property produces food - all kinds of vegetables, a large variety of fruit trees and berry bushes - and he is an advocate for traditional uses of the suerte, or land between the acequia and river. The altito, just below the acequia, is where the fruit trees grow best. Below that, la joya, is where the most fertile land is reserved for vegetables. Then comes las vegas, the summer pasture for animals, and finally, la cienega, the wetlands next to the river. He encourages farmers to diversify their crops and develop high-value crops that can find niche markets. Felicite Fonseca, a young woman relatively new to the area (she first lived in Taos with her parents when she was in high school) grows a variety of vegetables on the plot of land she rents from one of her neighbors in Apodaca. She sells most of her produce in Santa Fe, but she also serves as the manager of the Española Farmers' Market, which is open on Mondays from June through October near the town square. She points out how important the market is for local people to obtain fresh produce, especially families on the WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program, where families with young children receive money to buy fruit and vegetables. She and Lynda Prim are currently exploring the possibility of initiating a Community Supported Agriculture project, where customers pay a monthly fee and are guaranteed a certain amount of produce from the growers' gardens. They want to include Bob Petterson, who is developing solar systems for his large greenhouse to extend the growing season to a full year. There are many other growers in the Valley, many of whom are well known throughout el norte, like Stan Crawford of Dixon, whose garlic is renowned, and Eremita and Margaret Campos of Embudo, who specialize in many varieties of tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers. But according to Felicite, there are many more growers who sell their corn, chile, grapes, and apples to only family and friends. They continue the traditions of their ancestors and ensure that their lands remain productive and the acequias remain intact. ANNOUNCEMENTS• The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) released the Record of Decision on The Rio Grande Corridor Final Plan on January 4. The Final Plan will be available in the Taos Field Office at the end of January upon request (758-8851). This Final Plan is a "refinement" of the Proposed Plan/Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) that was released in August of 1998. Four formal protests and 32 informal protests were filed during the protest period of the FEIS. According to the BLM there were no changes added to the Final Plan based on the four protests, while several changes were included based upon the informal protests. Most of these changes appear to be related to boating management on the Rio Grande, including changes in numbers of boaters and length of boating season. To the surprise of members of the El Bosque Preservation Action Committee, the boating season extension applies to the spring as well as the fall season. The Final Plan will be subject to administrative appeal. La Jicarita will review the Plan in the next issue. • A coalition of New Mexican labor and human rights groups is sponsoring a "Solidarity LaborFest, a Gathering of Working Families" in Santa Fe on Monday night, February 21, at 7:00 pm at the NEA Building, 130 Capitol Street. Nationally known entertainers Charlie King and Karen Brandow will provide a night of music and solidarity. Ticket prices are $10 for adults and $5 for children and are available at 208 Griffin Street, Santa Fe, 992-8477. • The Quivira Coalition is sponsoring "An Evening With Sid Goodloe, Rancher" on Wednesday, February 23, at 7 p.m. in Santa Fe at the Unitarian Church. Sid's Carrizo Valley Ranch, located near Capitan, has been a model of progressive ranch management since he began operating it in the 1960s. In 1998 he established the Southern Rockies Agricultural Land Trust to protect farm and ranch land in perpetuity through the use of conservation easements. For more information, call 820-2544. The U.S. Forest Service at a CrossroadsBy Dan QuinnReprinted from Resources, published by Resources For The Future, with author's permission. Special thanks to Gabino Rendón of the Northern Research Group for bringing the article to our attention. It deals on a more general level with the issues we raised in the December La Jicarita issue regarding the future of Collaborative Stewardship. For 900 million visitors a year, the 191 million acres of forest and grasslands controlled by the U. S. Forest Service are a vast playground for camping, hiking, and other outdoor activities. For conservationists, these lands are home to dozens of species of endangered plants and wildlife, as well as the headwaters for one-fifth of the country's fresh water. And for industry, the Forest Service's holdings contain a vast bounty of oil, minerals, timber, and land for grazing. The U. S. Forest Service has long tried to maintain an uneasy truce among these competing interests. Its central mission, according to legislation passed in the mid-1970s, is protection of "the multiple use and sustained yield of the products and services obtained [on Forest Service land]" . . . and "the coordination of outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, wildlife and fish, and wilderness." In other words, the Forest Service is required to be all things to all people. That daunting mission would change substantially if the recommendations of a recent advisory committee, appointed to review the Forest Service mission, are adopted. The report of the 13-member "Committee of Scientists" - which included RFF [Resources For The Future] Senior Fellow Roger Sedjo - says that "ecological sustainability should be the guiding star for the stewardship of the national forest." Upon its release last spring it was immediately hailed as "a new planning framework for the management of our forests for the 21st century" by Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman, whose department oversees the Forest Service. But Sedjo believes the committee has overstepped its charge. By giving preeminence to preservation of biodiversity, the committee tips the scales away from mining, grazing, logging, or other commercial activities in a way that is directly counter to the Forest Service's legislative mandate. In a dissenting appendix to the report, Sedjo says that such a shift, if warranted, should not be decided by the committee of scientists but by the will of the American people, either through new legislation or some other means. And given the level of dissatisfaction on all sides about the agency's mission and performance, Sedjo believes Congress and the President should begin a dialogue that can help determine the public's will about the future direction of the Forest Service. Competing interests Originally hailed as a breakthrough in progressive legislation, the National Forest Management Act (NMFA) of 1976 was designed to provide a venue for conflicting parties to air their differences and come to consensus over management of the forests. Armed with such a consensus plan for each forest, the agency could make a budget request to Congress for funding them. In practice, however, this planning process quickly got off track. Consensus was hard to find at many forests, and the ability to tie up implementation of a plan through a lengthy appeals process has left some areas without a management strategy for more than a decade. Further complicating the agency's job has been a series of court rulings over enforcement of the Endangered Species Act, which have in many cases curtailed the commercial use of Forest Service property. The courts and recent federal policy hold that the requirements of the Endangered Species Act are overriding, so that if conflicts arise between the Endangered Species Act and an agency's other government statutes, the act must dominate. Although it has not been formally articulated, former Forest Service Chief Jack Ward Thomas says that the mission of the Forest Service has evolved over time to the point where "public lands managers now have one overriding objective for management - the preservation of biodiversity." This has created a gap between the Forest Service's statutory mandate and the nature of its actual management and activities. Underscoring this contention is the fact that the amount of timber harvested from national forests is about one-fourth of what it was at its peak in the late 1980s. Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman appointed the committee of scientists in late 1997 and charged them with helping guide USDA's revision of its 155 forest plans, as is required every 10 to 15 years. This is a critical time in that process, as more than 150 million acres are scheduled for plan revisions within the next five years. The committee called for the Forest Service to develop more collaborative relationships with local communities and interest groups throughout the planning process; to use scientific assessments to inform the public and land managers in making decisions; to strengthen the connection between science and management by adapting land management practices in response to results from scientific monitoring of land conditions; and to integrate the budget more fully into forest plan implementation. But beyond these specific issues, Sedjo believes the Forest Service needs a new, better-defined mission and answer to long-term budget questions that were not addressed in the committee's report. A new mission? An overriding emphasis on biological preservation may signal the end for the Forest Service, Sedjo believes. Without a role to support the tangible industry that is now part of its mandate, the Forest Service's budget may lose some of its support in Congress. It is doubtful that the goal of biological preservation could command the kinds of budgets that the Committee of Scientists' report calls for to manage such a program. If the budget erodes, the Forest Service may be forced to scale back from active management to custodial management and protection, Sedjo says. One promising area is recreation, however. With a more aggressive program of user fees in place, recreational users of the national forest could provide major revenue support for management of the forests. A suc-cessful user fee program may allow Congress to reduce its support for forest programs, however, and there is no guarantee that emphasizing recreation will quell the arguments over the agency's role. Some recreational uses may not mesh with other objectives for the forests, including preservation of biodiversity. Another option may be to combine enhanced user fees with a system that cedes more responsibility for managing national forests to local officials. Such an approach could give greater voice to local residents in making management decisions. Some national environmental groups oppose such a plan, however, believing that decisions about the use of such national assets rightly reside in Washington. Although the right direction is not crystal clear, "it is clearly time to rethink the role and mission of the Forest Service," Sedjo says. Congress and the Administration should begin a national dialogue that engages the public in helping to provide a future direction for the national forests. |

Acequia Water Issues Before the 2000 State Legislative SessionBy Kay MatthewsAlthough the 2000 state legislative session is short and dedicated to appropriations, that doesn't mean there aren't substantive water issues on the agenda. In our semi-arid state, water management decisions are critical to every facet of our future, from urban growth and development to norteño economic viability. Both appropriations and memorials dealing with water management issues will come before the legislators, who are hopefully aware of the complex and far-reaching impacts of their decisions. Last year's bill to establish a state-wide water bank, introduced by Representative Pauline Gubbels and Senator Sue Wilson of Albuquerque, generated considerable controversy and eventually died in committee. Both legislators were extensively lobbied and educated by a coalition of irrigation districts, conservancy districts, and acequias who expressed their opposition to the bill because of its potential commodification of water and because it would encourage water to be transferred from its area of origin and out of agricultural use. It appears that Gubbels and Wilson will introduce another state-wide water banking bill this session, despite this opposition and the emergence of a Regional Water Banking Act that is currently being reviewed and amended by various water stakeholders. Acequia advocates are also concerned about the need for an appropriations bill to enable those acequias currently involved in the adjudication process to correct errors and omissions in hydrographic surveys through negotiation with the Office of the State Engineer (SEO). Last year Representative Ben Lujan carried an appropriations bill of $60,000 to help cover these costs, and is being asked to again carry an appropriations bill for this year. In addition to this request, the New Mexico Acequia Association is also asking Representative Lujan to introduce a Joint Memorial to support negotiation efforts in these adjudications and to ensure that if settlement agreements between acequias and the SEO are not reached, the SEO will not oppose the right of acequias to bring these errors and omissions before the appropriate court. This has become an issue because of recent SEO unwillingness to allow due process in unsettled errors and omissions cases. Another memorial that the NMAA is currently drafting would ask legislators to decline adoption of proposed changes by the Interstate Stream Commission (ISC) to regulations regarding loans to acequias for maintenance, upgrades, and rehabilitation. These changes, according to the ISC, would "improve collectability and better increase banker's judgement" on loan repayments, but have raised numerous red flags in the acequia community regarding the autonomy of acequia commissions and the unnecessary burden the regulations impose. When the new regulations were initially proposed, several articles in el norte newspapers quoted State Engineer Tom Turney as stating that the changes were necessary because of loan defaults. It was revealed, however, that only one-half of one percent of the total amount loaned since 1972 was unpaid ($70,000 out of $12 million). Acequia representatives object to the "menu" of loan repayment options proposed in the new regulations as unnecessary, in light of their excellent repayment record, and see them as basically a usurpation of the autonomy of acequia commissioners, who already possess full statutory authority as officers of the acequia to sign for loans and work out payment options within their community acequias. These "menu" options range from traditional acequia commission approval to requirements that real property be pledged for security or a promissory note be signed by the ditch commission accepting personal responsibility. There is a fear that the ISC would be able to leverage the more stringent requirements against acequias. During last year's legislative session State Engineer Tom Turney invited acequia representatives to talk about the state engineer's policy to deny transfers of water rights from north of the Otowi stream gauge to a new point of diversion or place below the gauge. This policy has come into question because of the application by the County of Santa Fe to transfer water rights from Top of the World Farms, near Questa, by means of an infiltration gallery located on San Ildefonso land north of the gauge. The gallery would collect water that would be piped by the county to areas south of the gauge. Turney was questioning whether there was general agreement within the acequia community that this transfer could open the door to transfers of agricultural water from el norte to the south and affect the terms of the Rio Grande Compact. A memorial was drafted that asked the legislature to endorse the policy of the SEO to deny water applications that move the point of diversion or place of use of water from north to south, but no action was ever taken. Proponents of the memorial believe it would strengthen the public welfare argument in the Top of the World protest, but because of the unique situation of several adjudicated acequia communities who own surplus San Juan-Chama water rights, any memorial introduced this year will have to address concerns about their ability to sell or lease these rights at some time in the future. La Jicarita will monitor these bills and memorials and write a follow-up article in the March issue. EditorialBy Mark SchillerIn 1997 the Western Water Policy Review Advisory Commission (created by a act of Congress and appointed by the president) concluded that taking into account "the costs of capital, labor and other factors of production . . . the value of water used for irrigation [in the Rio Grande basin] is no greater than zero." They further suggested that the water would be better used to "generate the bundle of goods and services with the greatest value or the highest level of jobs, incomes and standards of living." In 1999 Sam Hitt, president of the Santa Fe-based environmental group Forest Guardians said, "I'd like to point out one major problem here is that agriculture uses 90% of the water in New Mexico . . . . We're using a technology from the 19th century, flood irrigation. That's what's causing the degradation of our rivers." (See August '99 La Jicarita for a response to Hitt's statement.) Most recently, Edward L. Bale Jr. of Vadito, in a letter to the editor of the Albuquerque Journal North supporting the transfer of water rights out of agriculture to implement a ski area expansion, cited a 1960 study of the Embudo Watershed which claimed that acequias are "inefficient and wasteful of water." Bale went on to say that "since the study less land is under cultivation and there has been little, if any, improvement of the acequias." All of these statements, while claiming to be factual, are actually subjective, full of inaccuracies, and completely misleading. But what really concerns me is the "unholy" alliance they represent. The federal government, the "deep ecology" faction of the environmental movement, and the "wise use" movement have traditionally fought amongst themselves over the management of our natural resources. Now, suddenly, they've united in their denunciation of the acequias and agricultural uses of water rights. Why? Although their hollow justifications are diverse, their bottom lines are all the same: The northern New Mexico acequia community controls a large percentage of the water rights within our basin (from the Colorado border to the Otowi gauge) and each of these groups wants to acquire more water to underwrite their own "higher value" agendas. In an age that is dominated by science and technology, they presume that the values of people who think subsistence agriculture is the foundation of community and culture are antiquated and ridiculous. In his book of essays, The Unsettling of America, Wendell Berry chronicles the history of usurpation of agricultural lands and water rights in the United States. He writes: "Generation after generation, those who intended to remain and prosper where they were have been dispossessed and driven out, or subverted and exploited where they were, by those who were carrying out some version of the search for El Dorado [the Seven Cities of Gold or in Hitt's case The Garden of Eden]. Time after time, in place after place, these conquerors have fragmented and demolished traditional communities, the beginnings of domestic cultures. They have always said that what they destroyed was outdated, provincial and contemptible. And with alarming frequency they have been believed . . . ." The truth is that much of the biodiversity, culture, and economy of northern New Mexico are dependent, in some way, on the continued vitality of the acequias. Ironically, tourists (the people with the "highest level of jobs, incomes and standards of living"), sickened by corporate globilization's devastation of their own communities and dislocation of their lives, flock to northern New Mexico to experience the beauty of the landscape and the coherence of the culture created by the acequias. Moreover, both the acequias and agriculture are experiencing a period of rejuvenation. Parciantes are organizing regionally and state wide to implement water banking, water conservation, acequia rehabilitation, and advocacy programs. According to the State Engineer's Office there are over 5,000 irrigated acres in the Rio Pueblo/Rio Embudo watershed alone, not less than 1500 as Bale claims. Our watershed also contains the highest concentration of certified organic farms in the state, which testifies to the growing value added market (see Embudo Valley Farmers article, page 1). Acequias are the foundation of norteños' ties to the land and community; they should also be the cornerstone for future economic self determination. According to David Korten, an authority on the effects of development on rural economies: "Development needs to be about people getting greater control of their local resources and helping them use them more effectively to meet their own needs." The acequias, one of northern New Mexico's most precious resources, are under siege. If we don't build our future on their foundation the water will eventually be severed from the land. Once that happens, farms and ranches will be subdivided, rivers and forests will become playgrounds for the rich, and our children will either be cleaning motel rooms, flipping burgers, or searching for an "El Dorado" of their own. Picuris Pueblo and La Jicarita Valley Communities Once Again go to Legislature for Funding for Wastewater Master PlanState Senator Carlos Cisneros has introduced a capital outlay bill in the current session of the state legislature asking for $70,000 to fund a wastewater treatment feasibility study for the Pueblo of Picuris and neighboring La Jicarita Valley communities. This is the 5th year these communities have gone to the legislature with their request; last year, money was earmarked for the study but was vetoed by Governor Johnson. In a letter to Johnson and the state legislature, Picuris Governor Red Eagle Rael explained that the unincorporated communities in the Rio Pueblo watershed lack monies and opportunity to initiate economic development ventures to underwrite the costs of environmental protection from wastewater contamination. After their unsuccessful attempts to obtain financial support from the state, last year they applied for private foundation money to fund a feasibility study and received $25,000 in seed money to initiate the study. With Picuris Pueblo serving as the fiscal agent, the communities are working together to form a Regional Wastewater Authority and to complete a Wastewater Master Plan. The communities are seeking an additional $250,000. Of this sum, $70,000 is earmarked for the study and $180,000 is for the professional, technical, administrative and legal expenses to document and complete the project. The Master Plan will assist the communities in understanding wastewater treatment options as well as assist them in pursuing federal funding to implement a treatment system. Various types of wastewater treatment systems will be looked at, including a series of smaller treatment plants throughout the watershed area. The Plan will also help anticipate future regional needs by evaluating population growth, wastewater flows, and source water supply. The project will serve 14 communities over a 22 square mile radius. Several of Senator Cisnero's legislative aides were at the Peñasco community meeting on Friday, January 21, with U. S. Representative Tom Udall (see following column), and expressed their hope that the bill will make it through the session. Tom Udall Comes to TownU. S. Representative Tom Udall spent Friday, January 21, traveling el norte to talk about the drug prescription bill he is sponsoring in Congress that would require pharmaceutical companies to sell drugs to pharmacies at the same price they charge managed-care organizations. In Peñasco, folks wanted to talk about other health-related issues as well, such as the desperate need for comprehensive insurance for the working poor and self-employed who are not covered by HMOs. Although President Clinton is asking for money to include the parents of children on Medicaid in the same program, Udall predicted that we would be lucky to see this Congress pass the prescription drug bill, along with a patient's bill of rights. A group of people representing Picuris Pueblo and La Jicarita Valley Communities asked for Udall's support for state monies to fund a wastewater treatment feasibility study. The community has gone to the state legislature for several years now to fund a study to deal with watershed pollution but has never received the necessary funding. Udall expressed his support for their efforts, and two aides of State Senator Carlos Cisneros, who has introduced a capital outlay bill for a $70,000 study in the current session, were on hand to talk with the community representatives. Water quantity issues were also on peoples' minds, and Udall told the group that the thirsty cities downstream should "keep their hands off acequia water rights" in their attempts to quench their thirst. He specifically expressed his opposition to the proposed Top of the World water transfer whereby Santa Fe County would transfer agricultural water rights from north of Questa to the county via an infiltration gallery located on San Ildefonso tribal land. While these are not acequia water rights, Udall stressed that we need to respect the terms of the Rio Grande Compact which has traditionally protected water rights in the north. The Office of the State Engineer has to date never allowed the transfer of water rights from above Otowi gauge, near Pojoaque, to below the gauge. The infiltration gallery is located north of the gauge and the water would be piped to Santa Fe County south of the gauge. La Jicarita also spoke with Gerald Gonzales, Udall's chief of staff, about money to send a delegation of norteños to Washington to speak with legislators and environmental groups about the potential impacts of the National Forest Protection and Restoration Act (Zero Cut bill) on land-based communities in el norte. Udall's office had previously made the offer to find funding for a delegation, and Gonzales agreed to follow through on the pledge. |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2000 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.