|

|

|

Volume VII |

August 2002 |

Number VIII |

|

|

Editorial: Forest Service Foreclosure Prompts Ranchers' Rebellion By Mark Schiller Puntos de Vista By Lorenzo Sotelo |

Colorado Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Sangre de Cristo Land Grant Rights to Grazing, Firewood and Timber on the Taylor Ranch By Kay Matthews Northern New Mexico Health Corps Recruiting Positions By Juliana Anastasoff |

Editorial: Forest Service Foreclosure Prompts Ranchers' RebellionBy Mark SchillerDuring the second week in July officials of the Santa Fe National Forest (SFNF) ordered 275 grazing permittees on 86 allotments throughout the forest to remove most or all of their cattle from Forest Service land because severe draught has limited the growth of grasses and other forage. After touring ten allotments in the Jemez, Cuba, Coyote and Española Ranger Districts, David M. Stewart, Forest Service regional director of range land management, wrote a widely circulated e-mail stating: "What I observed on the SFNF . . . is the most horrible example of grazing administration I've ever experienced in 35 plus years with the Forest Service." Permittees, some of whom vowed to defy the order, countered that Stewart's evaluation was superficial and that they are being "scape goated" for conditions that are the result of years of SFNF mismanagement during which their input has largely been ignored. Moreover, they maintain that they are being singled out while other factors including recreational impacts and increasing numbers of elk are being ignored. In a resolution supporting the ranchers, the Rio Arriba County Commission claimed that ". . . the potential exists for the extinction of a way of life and culture" if ranchers are forced off SFNF lands and must sell their herds at a loss as a result.

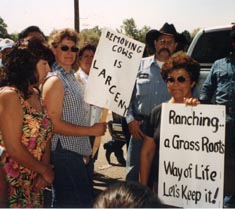

On July 15 about 100 SFNF permittees staged a demonstration outside the SFNF supervisor's office in Santa Fe to protest the removal order. Acting forest supervisor Gilbert Zepeda met with about a dozen of the protesters and told them he would not enforce his order until he had time to meet with the Range Improvement Task Force which was conducting an independent evaluation of the condition of 79 SFNF allotments. La Jicarita News spoke about this issue with John Y. Hernandez, a former range management specialist with the Forest Service and currently a grazing permittee in the Cuba area of the SFNF . Hernandez contends that the Forest Service should have been aware by February that this was going to be a drought year and should have discussed strategies to deal with depleted forage conditions at the annual operating plan meetings that are held with permittees in the early spring before any cattle are put on Forest Service land. He claims permittees have always been responsive in the past to Forest Service requests to reduce permits during droughts and that " no one should have been allowed to turn out their full numbers." He furthered claimed that range staff do not monitor grazing conditions closely enough and that Stewart's assessment of conditions only reflected what he could see in a"fast one day trip from a truck window [which] was very, very limited and definitely not representative of the allotments [he] was on. Worse yet, when this e-mail [Stewart's] came out all the Forest Service range personnel ran for cover like so many cockroaches when the light is turned on. They sent out letters kicking people off the forest in the middle of a grazing season with little or no data to back them up other than this e-mail from the regional office. The thing that really stands out to me is that there was little or no communication between the ranger districts and the permittees."

The demonstration bought the ranchers a week's reprieve. At the end of the week, however, Zepeda announced that the task force evaluation had done nothing to change his mind and he once again ordered the permittees off their allotments. At that point many of the permittees directed their efforts to salvage the grazing season at the Valles Caldera, an 89,000 acre ranch in the Jemez mountains which the federal government acquired two years ago. The property is mandated by Congress to be run as a working ranch and permittees hoped they could move their cattle on to the area, which hasn't been grazed for two years, for the remainder of the grazing season. On July 26 the ranch's board of trustees announced that they planned to allow somewhere between 687-2000 cows on to the ranch between August 17 and September 30. However, the permits will be distributed by lottery, which opens it up to all cattlemen, and the cost will be approximately six times per head what permittees pay on national forest land. Furthermore, the Santa Fe-based environmental group, Forest Guardians, announced it is prepared to challenge the board's grazing plan in federal court, making the Valles Caldera a long shot as an immediate solution for the SFNF permittees' dilemma. While there are obviously many factors contributing to this predicament, I think Hernandez hit the nail on the head: Once again the Forest Service's basic unwillingness to communicate and collaborate with forest-dependent community members is at the heart of the problem. The agency pays lip service to the notion of "collaborative stewardship", but it tacitly assumes that they're the "professionals" and often don't solicit, ignore, or severely limit public input. (Obviously Forest Service staff has a major problem communicating among themselves, which must also be addressed.) If, as Hernandez points out, range staff had toured the allotments with the permittees before the grazing season, some kind of equitable plan involving delayed entries and reduced numbers would certainly have limited the impact of the crisis which now threatens permittees' livelihoods and ability to maintain their traditional way of life, as well as the health of public range lands. By the same token, ranchers must be open to new ideas and bear in mind that only good stewardship will keep ranching viable. Permittees must also realize that they are only going to get as much accountability from the Forest Service as they demand and they must become more proactive in the long-range planning process. In the short term I think the government, which is constantly baling out unprincipled corporations to the tune of billions of dollars, has an obligation to compensate permittees for loss of income, either by paying them outright or by providing hay for the cattle which must remain on their home pastures. Forcing these ranchers out of business and off their land will have devastating economic, social, and environmental consequences which should not be an option. ANNOUNCEMENTS• Lynn Montgomery, mayordomo of the Acequia La Rosa de Castilla in Placitas, recently filed a formal protest of an application to transfer 11 acre feet of water per annum from three acres of land south of Isleta Pueblo to wells in a Placitas subdevelopment. This application is similar to several previous applications that transfer ground water from Rio Grande agricultural lands to wells many miles away that will underwrite residential development. Montgomery's protest claims the transfer will contribute to overpumping of the Rio Grande basin aquifer, impair the future of his acequia, and contribute to the loss of agricultural lands. For further information about the protest you can call Montgomery at 867-9580 or e-mail him at tawapanm@mm2k.net. • A report called Taking Charge of our Water Destiny: A Water Management Policy for New Mexico in the 21st Century was recently released and is available at 1000 Friends of New Mexico, 302 Aztec St., Suite B, Santa Fe, NM, 87501, 986-3831. The report, written by Consuelo Bokum of 1000 Friends, environmental attorney Letty Belin, and New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Minerals hydrologist Frank Titus, makes recommendations to the state legislature and state engineer for management of water use: * Development of a statewide, comprehensive water plan that integrates land-use planning * Permitting and regulation of domestic wells * Funding to complete statewide water adjudications * Reassessment of application of priority system

|

Colorado Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Sangre de Cristo Land Grant Rights to Grazing, Firewood and Timber on the Taylor RanchBy Kay MatthewsThe people of the San Luis Valley in southern Colorado had much to celebrate at the July Fiestas de Santa Ana y Santiago: It took 21 years, but they finally won their fight to retain grazing, firewood gathering, and timber harvesting rights on the 80,000 acre Taylor Ranch. On June 24th the Colorado Supreme Court issued a decision granting the landowners, who are the successors in title to the original settlers of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, these access and use rights on former grant lands now under private ownership. This decision overturns previous trial court and court of appeal decisions that denied the landowners these rights. According to Denver lawyer Jeff Goldstein, who has worked on this case since its inception, this victory is the "foremost property case of its type to be decided in 50 years" and may well have application all over the world in indigenous land claims. What it means for the people of the Culebra River villages and vara strips in the San Luis Valley, which could include 1,000 families, is that they now have the opportunity to once again work collectively on the land for the common good.  The Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, known as the Taylor Ranch, above San Luis, Colorado That, of course, was the intent of the original settling of the Sangre de Cristo grant. In 1844 the governor of territorial New Mexico deeded the original one million-acre grant to two Mexican nationals, who died during the Mexican-American War. After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war and promised to protect the property rights of former Mexican citizins, including honoring both Spanish and Mexican land grants, the Sangre de Cristo grant ended up in the hands of Carlos Beaubien. In the 1850s, Beaubien recruited farm families to settle the Colorado portion of the grant (it extended into northern New Mexico); town lots for housing and varas, or arable strips of land were allotted to families for farming, and common lands were provided for hunting, wood gather-ing, grazing, recreation, and timbering. In 1863 Beaubien wrote what came to be called the Beaubien Document, which was critical to the findings of this case. In this document Beaubien granted the settlers access rights to the commons land as well as issuing deeds to their farmland. Beaubien died a year later, but the new owner, William Gilpin, Colorado's first territorial governor, continued to provide deeds to settlers and recognized the use rights stipulated in the Beaubien Document. The settlers and their descendants continued to exercise their access rights until 1960 when the ranch was bought by Jack Taylor, a North Carolina lumberman, whose deed said that he took the lands subject to "claims of the local people by prescription or otherwise to right to pasture, wood, and lumber and so-called settlement rights in, to, and upon said land." However, Taylor began to deny access and built fences to keep people out. He filed what is called a Torrens title action, a Colorado statutory title procedure designed to disenfranchise aboriginal rights, and the US Federal courts upheld this action, denying the local landowners access rights. The current case began in 1981 when a group of local landowners filed suit in Costilla County District Court asserting their settlement rights to graze livestock, gather firewood and timber, hunt, fish, and recreate. They argued that their settlement rights stem from three sources: Mexican law,prescription, and an expressed or implied grant from Beaubien. In 1986 that court found in favor of the defendant, and in 1991 the court of appeals affirmed this decision (for further information regarding these decisions go to www.southwestbooks.org/sangredecristo.htm). Finally, in 1994 the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs were entitled to a hearing on their claims that they had been denied their due process right in the 1960 Torrens action because they were not named or served in that action. After a trial on that issue, which again eneded in defeat, and another appeal to the Colorado Court of Appeals and then to the Colorado Supreme Court, on June 24,2002, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the plaintiffs. The Court agreed with the lower courts that because the grant was settled after the Mexican-American War, the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo did not apply under Mexican law. But the court recognized that the Beaubien Document, supported by Gilpin's agreement and other evidence, guaranteed a prescriptive easement to the landowners. Noting that Beaubien wrote this document to honor his commitment to settlers he had persuaded to move hundreds of miles to make new homes in a wilderness, the court declared: "It would be the height of arrogance and nothing but a legal fiction for us to claim that we can interpret this document without putting it in its historical context." One last legal hurdle remains: a ruling on a brief submitted July 15 that asks the court to recognize the class of people initially identified in the lawsuit as having use rights, which includes families of the traditional villages of the Culebra River drainage originally under the common ownership of Beaubien. A previous trial court ruling had limited the names to seven landowners identified by Taylor in the abstract title to his land. Goldstein has asked the court to expedite a ruling on this issue. Goldstein emphasizes that these recognized prescriptive rights are easement rights, not ownership rights, and that now his clients can come together to form an organization to establish equitable use, a monitoring program, and mediation procedures. "I am so relieved to be talking about how the landowners are going to be using the land rather than if they ever had the right to use the land." During the fiestas celebration the folks in San Luis brainstormed with the lawyers about what their next steps should be in determining management policy and negotiating with the current Taylor Ranch owner Lou Pai. As Maria Mondragon Valdez, a longtime activist involved in the suit and wife of one of the plaintiffs, says, "The devil is in the details and we have our work cut out for us figuring out how to make 19th century traditional use rights fit 21st century reality." She explained that it may be difficult to exercise timber harvesting rights on lands that under Taylor's ownership were extensively logged by corporate companies "who tore apart the landscape." The nature of the community has also changed since Taylor acquired the ranch and closed down access. According to Valdez, some of the area ranchers had to leave because of a lack of grazing lands and access to timber resources, and many of the newer landowners would rather access the ranch for hunting, fishing, and recreation, rights that were not included in the decision. Ironically, one of the Supreme Court justices wrote a dissenting opinion arguing that the Beaubien document substantiates that the settlers use rights also include access for fishing, hunting, and recreation, and that the court decision should have also recognized these rights. He cited reports of Michael Meyer, professor emeritus at the University of Arizona and Marianne Stoller, professor of anthropology at Colorado College, that recognized that hunting, fishing and recreation, along with grazing, firewood gathering, and timber cutting, are all included in the use of common lands. Goldstein says it is unlikely his clients will choose to appeal the decision to include these additional rights. Negotiating with current owner Lou Pai isn't going to be easy, either. Pai, who bought the ranch several years ago under the guise of three limited-liability corporations, is a multi-millionaire former Enron Corporation executive who sold his company shares between 1999 and 2001 for $353 million before the stock collapsed. Although he is not currently being investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission, he is named in dozens of shareholder lawsuits. Since he bought the ranch - now officially called Jaroso Creek Ranch and Culebra Ranch - he has beefed up security and vigorously pursued trespassing complaints. At a demonstration last spring, local community activists expressed concern over his efforts to acquire more land and water rights and the fact that Pai is connected to such high-powered corporations like Enron. Valdez concurs: "Pai represents a globalization movement, not the good old boy network that Taylor represented." Pai has employed some local people to restore portions of the degraded timber lands on the ranch, and Valdez and Goldstein remain optimistic that the people of the valley will succeed in their efforts to develop a plan to exercise their use rights. They both look forward to discussions and possible collaboration with northern New Mexico land grant heirs whose ancestors managed their common lands for hundreds of years, and with community organizers who have been involved in management issues with public lands agencies. They see opportunities for setting up non-profit community development corporations that could establish woodlots and grazing associations that could benefit the local community. But for now they want to savor this victory that is the result of a hard fought battle - a battle that both drained and empowered a community: "We don't want any outside consultants, academics, or especially Lou Pai determining our future. We can do it ourselves," says Valdez.

Northern New Mexico Health Corps Recruiting PositionsBy Juliana AnastasoffThese days, many people are reflecting and talking to others about what they care about and value.They are asking how, as individuals and communities, can we support and serve one another. Communities in Northern New Mexico and across the globe are rich with histories and traditions of service. Some of the ways that people serve is by volunteering through organizations or through their faith communities. There have been several public programs since the 1930s that have rewarded service with educational opportunity. The Citizen Conservation Corps, the GI Bill, the Peace Corps, VISTA, and AmeriCorps are some of these programs. The Northern New Mexico Health Corps (NNMHC) is an AmeriCorps program that is part of Health Centers of Northern New Mexico. Each year we recruit 18 adults of all ages to serve in clinics, schools and community-based organizations in the Peñasco Valley, Embudo, the Española Valley, Santa Fé County, Anton Chico, Las Vegas, Taos, and Chama. We look for people who have worked in health care or social services before, or who are considering a career in a health-related field. Health Corps "members" enlist for an 11-month term of service and are placed at a site where they provide services that otherwise would not be there. Some help with applications for free or low-cost insurance and medications. Some provide outreach to and advocacy for people who need care but aren't getting it. They also provide health education to children and youth, moms and children, elders, and people with chronic diseases. In exchange for their service, members receive a cost of living stipend every two weeks, health insurance, childcare reimbursement (if eligible), student loan forbearance, and an educational award of $4,725. One of our main goals is to provide members with an experience that inspires and helps them to pursue or continue a health career, to use their education award for the training and education they need to do that, and to then serve their community as a health care or human services professional. Health Corps members have many opportunities for mentoring at their sites and at trainings. Also, they spend up to twenty-percent of each week in training on issues such as community development, diversity and inclusion, conflict mediation, citizen participation, and leadership. They also learn about interventions to address some of our toughest rural health challenges. Training is reinforced with service-learning projects, where we work with community partners on health fairs, clean-ups, beautification projects, gar-dens, emergencies, and celebrations. These collaborations strengthen relationships between people and organizations, and they help deepen our team's understanding of community health and well-being. Hopefully, they also plant seeds in members that will yield a life-long commitment to service. The Northern New Mexico Health Corps is now recruiting for our new program year that begins in October. For more information about joining the program or being a site host, please call our office at (505) 747-5921. Juliana Anastasoff is a health educator and Program Director of the Northern New Mexico Health Corps. She lives with her family in Chamisal. Agua Caballos Projects Record of Decision Finally ReleasedThe Record of Decision and Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Agua Caballos Proposed Projects was released on June 3, 2002. This project in the Vallecitos Sustained Yield Unit has long been in the making: public involvement began in 1992; two Draft Environmental Impact Statements (DEIS) were released, in 1995 and 1999; a supplement to the DEIS was issued in 1999; and many public meetings and field trips were held over the course of the project. The second DEIS was released to comply with the amended forest plan and the supplement to the 1999 DEIS was issued in response to discrepancies regarding the actual number of road miles that would be needed to implement the Preferred Alternative. Two new alternatives were included in the supplement that included no new road building, and an Alternative G was developed that keeps road building to a minimum while still meeting the purpose and need of the proposal. Alternative G is now the Preferred Alternative and includes the following prescriptions: • 6.4 million board feet (MMBF) of sawtimber (6.1 MMBF within the Unit to local operators and .3 MMBF outside the Unit) • Allocation of 20% of the analysis area to old growth • Construction of 3 miles of new road • Reconstruction of 16.7 miles of existing road • Creation of 20 miles of temporary road to be closed immediately following implementation • Closure of 43 miles of existing road following project implementation • Commercial thinning of 28 per cent of 2,379 densely stocked acres • Precommercial thinning of 1,693 acres • Prescribed burning of 1,986 acres of treated stands The decision is subject to appeal, which must be filed within 45 days from the date of publication. For additional information, contact Kurt Winchester, El Rito District Ranger, 581-4554/4555. La Jicarita News will write a more in-depth analysis of the Agua Caballos final EIS and any appeals that may be filed in the next issue.

The September and October issues of La Jicarita News will be combined. Look for the next issue at the beginning of October. |

Home | Current Issue | Subscribe | About Us | Environmental Justice | Links | Archive | Index

Copyright 1996-2002 La Jicarita Box 6 El Valle Route, Chamisal, New Mexico 87521.