Water For All: Organizing

Against the Privatization of Water

By Kay Matthews

"Remember, we're not in the business of construction,

we're in the business of making money."

These are the words of Steven Bechtel of Bechtel

Corporation, the company that tried to privatize the water

system in Cochabamba, Bolivia, until the citizens kicked

them out of town and took back their water during La Guerra

del Agua (see La Jicarita, July 2002). Elizabeth Peredo of

the Fundación Solón of La Paz, Bolivia, told

the wonderful story of la gente's victory in Cochabamba at a

recent board retreat of Agricultural Missions at Ghost

Ranch. Agricultural Missions is an ecumenical organization

whose mission is "To work in partnership with people of

faith and conscience around the world to end poverty and

injustice that affect rural communities." This year the

group is focusing on the geopolitical importance of water

and the global crisis faced from its limited availability

and privatization.

La Jicarita News was invited, along with other New

Mexicans, to join in a dialogue about water with Peredo,

Ryan Case of Water Stewards Network, and José

Luís Montes of Chihuahua, Mexico. Case presented an

overview of how water corporations, financial institutions,

professional organizations, and the media are promoting

public/private partnerships and free market solutions to

water scarcity. Organizations like the Global Water

Partnership, the World Commission on Water, and the World

Water Council, under the protective umbrella of the United

Nations, work behind closed doors to define water as an

"economic good rather than a human right." The International

Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are helping move

towards water privatization by requiring that loans provided

to developing countries be tied to the privatization of

water, while the World Trade Organization (WTO) facilitates

protection for corporations like Bechtel involved in this

privatization.

In 2004 the World Bank will spend $4 billion on big

technology water projects. A particularly egregious example

of how we are moving away from local, sustainable water

delivery is the Tehri Dam project near the headwaters of the

Ganges in India. This project, first conceived in the 1970s,

will potentially kill the river, submerge an entire

agricultural valley displacing as many as 100,000 people,

and will probably produce far less electricity than

initially estimated. Water in the affected villages has

already been privatized, owned by the French corporate giant

Suez, while the electricity generated will travel hundreds

of miles to New Delhi to provide drinking water and

irrigation for sugar crops. The people of Tehri have so far

refused to leave their village, despite the lack of water

and the bulldozing of their homes. Case summed up this

depressing scenario of privatization: "The global economy is

held together by one principle: providing profit. You cannot

provide water sustainably to people and make a profit at the

same time."

Elizabeth Peredo

Elizabeth Peredo's presentation was another graphic

example of this scenario, but at least in the short term, a

victory for the people. Even though Bechtel fled the

country, Bolivia is now being sued by the conglomerate to

recover $25 million of "potential lost profits" under the

protection of the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). Peredo is hope-ful that the new Bolivian government

elected last year will proactively fight this suit against

its people. She also pointed out that the struggle in her

country has helped make people more aware of conserving and

protecting their water resources (a coalition between rural

and urban communities has formed to protect water at its

source) and has empowered women, who were on the front line

of the struggle.

In the afternoon, José Luís Montes of the

Solidarity Task Force of Human Rights in Chihuahua, Mexico,

spoke about how the 1944 treaty between Mexico and the

United States is pitting Texas ranchers against Chihuahuan

farmers and others of the Rio Concha watershed, whose crops

and animals are dying and are even without drinking water.

He stressed that the drought "doesn't respect borders" and

that the Texas ranchers must release water into the Rio

Concha so the indigenous people can manage their own

resource.

A panel of New Mexicans, including Richard Moore of the

Southwest Network for Environmental and Social Justice in

Albuquerque, Germán Agoyo of San Juan Pueblo, Kathy

and Gilbert Sanchez of San Ildefonso Pueblo, and Kay

Matthews of La Jicarita News, provided an overview of water

issues in New Mexico, explaining how these same forces

described by Case, Peredo, and Montes affect the equitable

distribution and management of water in our state. They all

stressed the importance of community control of water, but

recognized that conflicts among constituencies - pueblos,

non-Indian rural communities, environmentalists and the

state - still largely drives the dialogue.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

The Cry of the Poor

A Call to Peacemaking

The 22nd annual Prayer Pilgrimage for Peace from

Chimayó to Los Alamos will take place on Saturday,

April 17. The guest speaker will be Sister Dianna Ortiz,

native New Mexican, missionary to Guatemala, and founder and

director of the Torture Abolition and Survivor's Support

Coalition (TASSC). The schedule is as follows:

8:00 am: Gather at Holy Family Church in Chimayó,

opening prayer with Gerald Nailor, Governor, Picuris Pueblo,

send runners to Los Alamos.

9:00 am: Mass followed by 3 mile Walking Prayer

Pilgrimage to Chimayó Santuario led by Los Hermanos

of Northern New Mexico.

11:00 am: Interfaith sharing and bread circle at

Santuario and lunch.

1:00 pm: Car pilgrimage to Ashley Pond at Los Alamos.

1:45 pm: Music, dances of peace and reflections at Ashley

Pond.

2:30 pm: Welcoming of runners, blessing of earth with

Governor Nailor, reflections offered by Sister Ortiz,

closing prayer and circle for peace around Ashley Pond.

Pilgrims should wear comfortable shoes and layered

clothing and bring a sack lunch. Sponsored by the Office of

Social Justice, Archdiocese, Santa Fe. Call 831-8205 or

David Fernandez at 758-7608.

• The Second Annual Conference of the Adobe

Association of the Southwest will take place on May 21, 22,

and 23 on the campus of Northern New Mexico Community

College in El Rito. The conference will look beyond just the

mud and bricks of adobe at some of the cultural, social, and

economic impacts, including the contribution of women. It

will also address the following topics: affordable adobe

construction; thermal properties of earthen materials;

historical buildings of note in the United States;

historical architects/designers of note; historical

developers/ planners of note; new projects; adobe education;

manufacture and supply of construction materials. To

register, contact Quentin Wilson at 505-581-4156 or

qwilson@mail. nnmcc.edu. The schedule is as follows:

Friday, May 21

11 am to 1 pm: Registration

1:30 pm to 4:40 pm: Session I

5 pm to 6:30 pm: Dinner

7 pm to 9 pm: Social hour

Saturday, May 22

9:30 am to 12 pm: Session II

1:30 am to 12 pm: Tour

7 pm to 9 pm: Session III

Sunday, May 23

9:30 am to 12 pm: Session IV

A Better New Mexico is Possible!

Countering Globalization and Building our Local

Economy

April 30-May 2, 2004

Friday Evening / Saturday / Sunday

at the Forum, The College of Santa Fe.

Come hear how the global economic system affects us

locally. Discuss alternative visions and sound strategies

for building life-affirming economic structures. Strengthen

your organizing skills and join with others to implement

initiatives that build our local economy. Together we can

create a vibrant New Mexico for our children!

With Many Leading New Mexican Community Organizers.

Panels will include: Global versus Local Food Systems,

Border/Labor/Immigration Issues, Land Grants and Acequias,

Environmental Racism, Building Energy Self-Reliance, Ecology

and Human Health, Supporting Peoples‚ Movements in the

"Third World," and much else!

And Internationally Renowned Voices: Onesimo Hidalgo,

CIEPAC (Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y

Políticas de Acción Comunitaria); Kevin

Danaher, Global Exchange; Helena Norberg-Hodge,

International Society for Ecology and Culture; Michael

Shuman, author of Going Local

Cost: Full Program: $100; Fri. or Sat. Eve: $17;Per Day

Rate (including evenings): $60; Per Session Fee: $10..

Inquire regarding student rates and scholarships.

Registration at www.nonviolenteconomics.org or by calling

the Institute at 995-9793.

• The Online Civilian Conservation Corps Museum is

seeking stories about the CCCs, CCC Enrollees, Staff, or

Technical Advisors for publication in this online historical

resource. If you would like to participate please send your

stories, with name, company, number, and location, if known,

to CCC Collection, P.O. Box 5, Woodbury NJ 08096 or e-mail

JFJ museum@ aol.com.

• Drought and a growing population have made water

conservation and protection of water quality more important

than ever before. The next generation will be better able to

deal with the challenge if they start gaining skills and

awareness of water resources now. With this in mind, La

Jicarita Enterprise Community is hosting a water education

workshop for area educators on May 5, 2004 at the

Peñasco School. This free workshop will be

taught by Bryan Swain, New Mexico's Project WET Coordinator,

and Ryan Weiss, the Education Program Coordinator for Eight

Northern Indian Pueblos Council. Each participating teacher

will receive a personal copy of the Project WET Curriculum

and Activity Guide, which contains materials for more than

90 water education activities. During the workshop,

several of these activities will be presented, including

"Raining Cats and Dogs" (which emphasizes literacy and

geography), "The Incredible Journey" (on the water cycle),

"Pass the Jug" (on water rights and allocation), and

"Branching Out" (on watershed mapping).

Interested teachers should register by April 28th by

calling Ruby Lopez (Peñasco Independent School

District) at 587-2230, extension 2. For more information,

call Cordell Arellano (La Jicarita Enterprise Community) at

587-0074.

• Check out the new agricultural website

www.e-plaza.org (more on this project in the May/June

issue)

The Water Market Game

By Kay Matthews

Reprinted with permission from the El Dorado Sun

At the Santa Fe hearing on the State Water Plan in the

summer of 2003 environmentalists, acequia parciantes,

farmers, ranchers, and city residents all told the

Interstate Stream Commission (ISC - authors of the plan)

that unless growth in Santa Fe and Albuquerque is limited we

will run out of water - period. At the Las Vegas and Taos

hearings the same message was conveyed, this time from the

heart of acequia communities that could be the big losers in

a water market game. And at the three-day Town Hall meeting

in Albuquerque, it was pounded home even harder: no amount

of water conservation, water banking, water delivery systems

[see article on pages 4 and 5], desalination plants,

or combinations thereof is going to solve our water woes if

we don't do something to stop the developers from turning

Albuquerque into Los Angeles and Santa Fe into a desert

wasteland.

Planning staff at the ISC drafted the water plan at the

behest of Governor Bill Richardson (also mandated by the

state legislature in 2003). It took a year's worth of public

hearings and consultation with State Engineer John D'Antonio

and members of the Water Trust Board (WTB), comprised of

representatives of diverse constituencies including acequia

and irrigation communities, Native Americans,

environmentalists, and various state agencies. The final

draft version of the plan was presented to the governor and

the Interstate Stream Commission for their approval in

mid-December. Implementation of the plan is both statutory

(authorized by state statute) and legislative; the latter

will be necessary to fund state agencies responsible for

carrying out the plan's various components.

ISC director Estevan Lopez, in charge of the plan's

promulgation, brings experience as a Peñasco acequia

parciante as well as former Santa Fe County manager, dealing

on a daily basis with urban growth and development issues.

In an interview last February with La Jicarita News Lopez

said, "The criticism of cities is, where does growth end? Or

should we be looking at stopping growth? These discussions

need to be opened up even if they're difficult and

emotional. I don't know if this will provide solutions but

at least you start getting at some of the root issues

instead of one side saying, 'We can't have any more growth

because we don't have enough water,' and the other side

saying, 'You're just saying that so you can control growth.

Let's have a discussion about the growth, then."

While that dialogue did take place in many of the public

hearings on the plan, the final version largely ignores this

debate and devotes many pages to "making more water":

"creating" more drinking water with desalination plants;

conserving water through more efficient delivery systems;

banking water (temporarily reallocating water); and of

course, buying and selling water on the open market. A

policy statement in Section C.2 of the plan reads, "The

State shall promote water markets that enable the efficient

movement of water rights within the State in accordance with

the applicable legislative and legal safeguards." The plan

goes on to say, "As water demands from expanded existing and

new uses increase, the demand for marketing of water through

these voluntary transfers of existing water rights will

grow." (The word voluntary was added to the language in the

Draft Final.)

This is the direction water policy has been headed the

past 20 years: commodification and movement of water to the

"highest and best use", meaning, of course, whoever can come

up with the most money gets the most water. Currently

sitting as "Representative of the Environmental Community"

on the WTB, Denise Fort was chair of the Western Water

Policy Review Advisory Commission, a committee mandated in

1992 to define the federal role in water policy for the 19

western states. The report released by that commission,

Water Management Study: Upper Rio Grande River Basin,

states, "We recommend federal agencies in the [Rio

Grande] Basin do more to mitigate the constraints to

competition that keep water and other resources in low-value

uses while high value demands go unmet." The report goes on

to say that acequia associations and irrigation and

conservancy districts have exercised undue influence on

legislation pertaining to water distribution in the state

and the Rio Grande Compact "reflects the agrarian economy .

. . that existed at the end of the 1920s, not today's highly

urbanized economy." Even new innovations such as water

banking programs, which the 2003 legislature approved,

should, according to the report, only be supported by

federal agencies if they determine "that the bank will

facilitate voluntary transfer of water to highest-value

uses."

The commodification of water has long been a concern of

the New Mexico Acequia Association (NMAA), an advocacy group

of acequia parciantes and associations across the state. The

NMAA was instrumental in helping pass legislation last year

that allows acequia systems to bank unused water (water that

would be reallocated within the acequia system) and to adopt

a provision in their bylaws that gives commissioners the

authority to deny proposed water transfers if they would

impair the acequia's operation.

At the October 2003 hearing in Santa Fe on the Draft

Water Plan, Paula Garcia, director of the NMAA and

representative of acequia parciantes on the WTB, asked that

the water plan protect acequia water rights under the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo and that acequia communities be treated

as a distinct entity along with Native American pueblos. She

objected to the language in the plan that essentially

defines the Office of the State Engineer (OSE) as a

"facilitator" of water markets rather than a "regulator" in

this process that threatens the water rights of rural

northern New Mexico. Trudy Valerio Healy of Arroyo Hondo,

the WTB representative of irrigation districts, shares

Garcia's concerns. "Some rural areas may sell their water to

urban areas, then become ghost towns," she warned.

ISC director Lopez and State Engineer D'Antonio point out

that the plan is a "working document" that will evolve over

time to incorporate public concerns and technical

information that continues to be gathered. In response to

Garcia's concerns, which were raised by many others at all

the public meetings, the final version references that

"acequias assert certain protections under the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo" and that "Nothing in the State Water Plan

will impair or limit the claims that these Native American

and acequia water-rights holders assert."

In the meantime, the OSE continues to adjudicate stream

systems, which essentially privatizes water rights that have

been used as common rights in acequia and pueblo communities

for hundreds of years. The adjudication process is also an

adversarial one, pitting the state against individual water

users who must defend their water rights in a lengthy,

litigious process that takes years to complete.

This process of privatization has larger implications in

the global water market. As Maude Barlow points out in her

definitive book on water privatization, Blue Gold: The Fight

to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's Water, "Citizens

of the most privileged countries simply take water for

granted or are able to buy it . . . [and] their

lifestyles - SUVs, lawns, and golf courses" are a leading

factor in "consumption disparity between rural and urban

areas, the rich and the poor." Global water cartels will

certainly not provide water to all, and those they do will

pay dearly for it, like the citizens of Cochabamba, Bolivia,

who successfully fought off a consortium led by Bechtel

Corporation (now making millions in Iraq), with whom the

Bolivian government contracted to take over the municipal

water system [see article on page 1].

Could this be the scenario in New Mexico? Certainly the

tension between urban and rural and rich and poor will be

exacerbated as water is increasingly commodified and sold on

the open market. That's why so many of the policies

implemented by our city councils and county commissions and

now codified in the State Water Plan make little sense to

the people who came to the Water Plan hearings and told the

planners that New Mexico is a desert state with a carrying

capacity that has already been exceeded.

Albuquerque and Santa Fe want to build diversion dams to

access San Juan/Chama water rights that may soon be

nonexistent. If the current drought continues, the flow from

these rivers into Heron Reservoir may be reduced to a

trickle, especially in light of the fact that upstream

Navajo rights are senior rights that will keep the water

from ever entering the diversion tunnel. Buying acequia

water rights, which Healy fears will turn our rural villages

into ghost towns will also turn our tourist economy into a

fond memory - or not so fond for some folks - once the

fields, wildlife habitat, and open space the acequias

support dry up. If "management" of our water resources -

that is, conservation, new diversion projects, the purchase

of water rights, new technology, and conjunctive use

(combined surface and ground water) - merely facilitates

unlimited residential and commercial growth, we are indeed

headed towards social and environmental collapse.

To buy into the "grow or die" argument is to fail to

recognize the difference between economic growth and

economic development. Several years ago, Maria Varela,

longtime New Mexico community activist, wrote a paper on

this issue. "Growth increases the amount of money running

through a community's economy but may not increase that

economy's capacity to steer its own direction. Growth is

characterized by dependence on outside capital, technologies

and management talent. Economic development, conversely,

increases the capacities of the people in the community to

attract and pool capital and acquire technologies and

management skills. Most of the wealth stays in the

community." Our finite water resources must be used to

support economic development, not growth, and until the

powers that be also acknowledge this concept, the State

Water Plan is, as one citizen commented at the hearing on

the draft plan, "full of sound and fury, signifying

nothing."

|

Puntos de Vista

By Orlando Romero, Nambe Resident and Historian

Editor's Note: What follows is the resignation

letter that Vice-President Orlando Romero of the Pojoaque

Valley Water Users Association wrote President David Ortiz

on February 9. Below the letter is an explanation of the

proposed Aamodt settlement.

Dear David:

Regarding our conversation of February 4, 2004, and for

the record, the following points are the reasons that lead

me to resign my position on the board of the PVWUA.

The so-called settlement or resolution of the Aamodt case

with the Pueblos has so many unanswered issues, questions,

ambiguities and is so poorly conceived that I for one cannot

support the results. My rationale is based on the

following:

1. Secrecy. Although we were advised by our legal counsel

that the settlement hearings had to be held in secrecy

because of their political nature, we do live in a democracy

and in a democracy, agreements signed and conducted in

secrecy usually are not worth the paper they are written on.

People in this valley, including Chupadero, Tesuque,

Cuyamungue, Pojoaque, Nambe, Jacona, El Rancho, etc., are

very well aware that all hearings were held in secrecy and

that they had no input regarding their water rights,

especially having to give up their wells. How do we justify

this lack of democracy?

2 Priorities. Our legal counsel has advised us that if

the Pueblos decide to call on the priority rights awarded to

them by Judge Mechem's decision, there will be no water left

for the non-Indians for either acequias or wells.

Politically, this would be a disaster for the Pueblos.

Thousands of angry water users would protest to their

respective county, state and federal representatives. In the

midst of a drought, while the Pueblos continue to water golf

courses, to use this rationale for settling or resolving

this suit is faulty at best.

3. Contractual Agreements. The broken gambling compacts

approved by federal and state governments with the Pueblos

are an excellent example why this settlement should not be

agreed to. Even as I write, gambling compacts are now, once

again, being renegotiated. The Pueblos have enormous

resources from their casinos for lawyers. How can we be

reassured that they won't come back, time and again, to

"renegotiate" this settlement?

4. Giving Up Our Wells. Explain the logic of having to

give up our wells and consolidate those rights in a water

"company" or city/county water association so that the

county can tap into and continue their uncontrolled growth.

Doesn't that defeat the purpose of trying to salvage the

stream flow of the Rio Nambe? And if Pojoaque Pueblo is

going to receive an additional 300 acre feet of water from

this deal, how are we as board members going to justify

these additional water rights, especially when the Pueblo

continues to water golf courses in the midst of a prolonged

drought while our valley folk have to give up their

wells?

5. Irrigators. Are we to believe that well users are

going to give up their wells so that the few who still

irrigate can keep irrigating? You know as well as I do that

the county has allowed prime irrigated land to be developed

into 3/4 acre home sites. There are now more well users than

irrigators.

6. Irrigation Wells. Why and who negotiated into this

settlement that "irrigation" wells are exempt from the rest

of the wells because they take their source water "directly

from the stream flow"? You know as well as I do that many of

these so-called deep irrigation wells are owned by very

powerful people and are nowhere near the source of direct

stream flow.

7. San Juan Water. As a researcher, historian and

small-time farmer, I am supremely aware that there is a huge

difference between paper water rights and real, honest

flowing water in a ditch or pipeline. San Juan water during

this prolonged drought is almost nonexistent. The Azotea

tunnel has realistically, for all practical purposes, been

shut off. Look at Heron Lake; it looks like a pond. And the

Navajos are next in line to get priorities off this flow, so

how can the city, county, state or feds base a settlement on

such a tenuous supply of water - unless the real intent is

to divert all our well rights to these massive new water

fields at San Ildefonso?

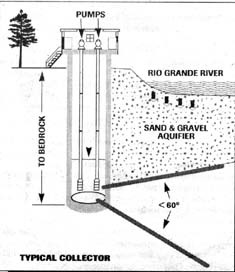

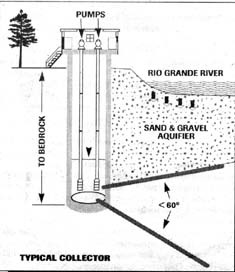

8. The Ranney Water Fields. The presumption that these

new "water fields" can take direct source water from the Rio

Grande with minimal filtration is very bad science. Ongoing

ecological studies are showing that the most sophisticated

water treatment plants cannot filter or treat antibiotics

and antidepressants that go through treatment plants and are

then returned to rivers and waterways. Above the proposed

Ranney water fields, the cities of Española and Taos

discharge their treated water into the Rio Grande. How can

we honestly tell the people of the valley and the county

that their new piped water is cleaner than the water they

get from their individual wells?

9. City/County Water Board. As I write this letter, the

Legislature is trying to pass a bill that would allow the

city and county to create a water board that would have

condemnation rights on our wells. Is this the same water

board that is proposed to run the Ranney fields system and

so-called Pueblo pipeline that does not exist yet? If not,

where is this new water board going to get its water? What

is its point of diversion?

And most important, our legal counsel, both in private

and in public, assured us that we were going to have the

right of refusal if we did not agree with the proposed

Aamodt settlement, especially regarding the issue of giving

up our wells. Why is this board and legal counsel advocating

this new water board that can condemn our wells? Is this the

back door way of telling us "accept the settlement or the

county will condemn your wells anyway?"

10. Hookups. How are we to pay for this new water system

after our wells have been taken from us? More taxes? How are

poor people supposed to pay for this "service"?

I hope you understand why I can no longer serve on this

board. I joined this board to serve my community. Instead, I

feel that I've been used by lawyers and politicians who

cannot or will not serve the needs of their clients or their

constituents I don't see much democracy in these

negotiations. Instead, there is secrecy and back door deals

in which I do not wish to participate.

Sincerely,

Orlando Romero

Editor's Note: Subsequent to Orlando's resignation

from the Pojoaque Valley Water Users Association, a new

group, the Pojoaque Basin Water Alliance (PBWA), was formed

by defendants in the Aamodt case to represent the interests

of well owners in the Pojoaque Basin. In its March 26 press

release, the Alliance "seeks a settlement which is fair and

equitable for all defendants." The group is trying to

educate the public about the potential effects of this

proposed settlement and the legal precedents it could set.

PBWA will hold its first public meeting on Wednesday, March

31, 7 pm, in the Frank B. Lopez Gym at Pojoaque Valley High

School. For more information contact Julia Takahashi at

455-7069 or Orlando Romero at 455-3315.

The Settlement Agreement

The proposed settlement to the Aamodt lawsuit, which is

the subject of Orlando's letter, refers to a lawsuit that

was originally filed in 1966 to determine the extent of

water rights of non-Indians and Indian Pueblos in the

Tesuque, Nambe and Pojoaque watersheds. Under the priority

system that has been adopted by the state of New Mexico,

those who first put the water to "beneficial use" have

priority in times of shortage. This means that the Pueblos,

which hold the senior most rights, could petition the court

to cut off diversions by junior water rights owners until

their full assessment has been met.

The settlement proposal identifies three tiers of

priority: first, the Pueblos of Tesuque, Nambe, Pojoaque and

San Ildefonso's existing water rights, which amount to 1,391

acre feet (an acre foot is approximately 326,000 gallons)

and their development rights to 2,269 additional acre feet;

second: the existing water rights (both surface and ground)

of approximately 2,200 non-Indian households within the

valley with the proviso that all existing domestic wells be

capped and those ground water rights transferred to a

proposed water delivery and wastewater treatment facility;

and third, 2,500 additional acre feet for future pueblo

development. In addition, the settlement calls for the

construction of a pipeline which would transport effluent

from the waste treatment facility to the Pueblo of Pojoaque

for irrigating its golf courses.

The proposed water delivery and wastewater treatment

facility will cost an estimated $280 million, of which the

federal government would pay $212 million. (This federal

funding has not been secured and hinges on Senator

Domenici's clout within Congress.) The diversion for the

facility (what Orlando refers to as the Ranney water fields)

would be on the Pueblo of San Ildefonso, which has not as

yet negotiated agreements to access that facility. Moreover,

the diversion would be above the Otowi gauge but would

service areas both above and below the gauge. Historically,

the State Engineer has not permitted water diverted above

the gauge to be used below the gauge. Water rights owners

above the gauge have expressed concern that this could set a

precedent that would allow municipalities and developers

below the gauge to shop for water rights above the

gauge.

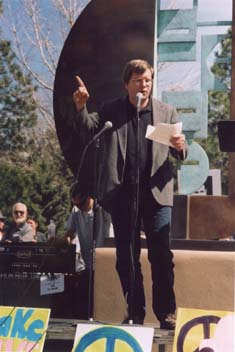

Marching to End the

Occupation of Iraq

On March 20 millions people in New York, San Francisco,

London, Rome, Tokyo, and Madrid rallied and marched to send

a message to the Bush administration that they oppose the

continued occupation of Iraq and other imperial wars being

waged around the world. In Santa Fe, hundreds of peace

activists gathered at the Roundhouse to listen to speakers

before marching to the Plaza with their banners, signs, and

chants, "Bring the Troops Home Now." Father John Dear,

activist priest and member of the Ploughshares community,

told the crowd about his plea to National Guard troops in

front of his house in Springer to lay down their weapons.

Santiago Juarez urged people to get out the vote in the

critical presidential election and sent organizers

throughout the crowd to register voters. Miguel Angel, of

the Las Vegas Committee for Peace and Justice, spoke of the

many wars and occupations the United States has perpetrated

around the world. And Chopper Sic Balls, a Santa Fe punk

band, exhorted the crowd to embrace the diversity of peoples

here at home and around the world.

Father John Dear

Santiago Juarez, director of P.A.C.E. New

Mexico

Edge Habitat family members Sarah, Mary, Aspen, and

friend Emmy

Who's Reading La

Jicarita?

Father John Dear

|